-

A Review of Larraín’s Neruda

Neruda, a “sacred monster”? Well, ask Roberto Bolaño. And yet: With his new film, Neruda, Chile’s master of the political gothic, Pablo Larraín, exhumes a sacred monster: namely, his nation’s 1971 Nobel Laureate, the poet Pablo Neruda. Hardly a biopic, Neruda focuses on a brief, if dramatic, period in its subject’s life—a fifteen-month period from January 1948 through March 1949 during which the poet, an elected senator and an outspoken member of the banned Chilean Communist Party, went underground, finally escaping over the Andes to Argentina.Read More

-

My Year in Books (2015)

I, too, dislike “best books” lists except when they bring me news of books I want to read but somehow overlooked, which is surprisingly seldom. Over 60-plus years of reading, beginning, as I recall, with Little Golden Books, I’ve developed enough self-awareness to guess correctly about 70 percent of time which books will bring me that mixture of pleasure and revelation that is my particular addiction.Read More

-

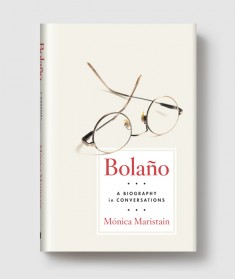

After Bolaño with Mónica Maristain

I look forward to Christmas like a little kid because I know that new books will come my way. I read mostly used books, a tactic aimed at keeping our household solvent, but over the past few years I’ve bought (or begged to have bought for me) each new book by or about Roberto Bolaño. The “about” books so far have proved illuminating in ways I didn’t anticipate. The one I’m reading now, which has occasioned this post, is Mónica Maristain’s Bolaño: A Biography in Conversations.Read More

-

Poetry and Arms

This morning, after watching and reading about the protests over 43 missing students in México, intense resonance from Roberto Bolaño: Hills shaded beyond your dreams. Castles dreamt by the vagabond. Dying at the end of any old day. Impossible to escape violence. Impossible to think of anything else. Feeble men praise poetry and arms. Castles and birds of another imagination. What has yet to take shape will protect me. And here’s the original: Colinas sombreadas más allá de tus sueños. Los castillos que sueña el vagabundo. Morir al final de un día cualquiera. Imposible escapar de la violencia.Read More

-

Bacon Flavored Erasure Poetics

I’m sitting in bed at the moment next to my lovely wife, who’s reading a holiday catalog. She is fixated on a spread peddling bacon-themed gifts. Bacon-strip ties. Tee shirts imprinted with images of bacon. Bacon Christmas ornaments. No shit. She remarks, “This is the most moronic thing I’ve ever seen. Who is this stuff aimed at?” I don’t answer because I’m engaged in something even more idiotic. I’m reading about a book called Gentle Reader!. It is a product generated by three contemporary poets through a process of erasing passages from certain works of Romantic-era writers.Read More

-

Friday Notebook 02.18.2011

[I found a scrap of paper under my car seat with these lines scrawled on it, from last summer, as I recall] A chirring fires up in the locust treeas if a hand switched on a lamp of sound. * The tyrant resigns and flees.The ancient square throbswith exultant crowds. Reportersfor State TV recant the liesthey told all those years,and are forgiven. Far away,the tyrant has wrapped himselfin a cloak of rage and fear-sweat;he smells like his subjects didfor three decades.Read More

-

More on Exile

Apropos of Roberto Bolaño’s speech on the subject of exile, which I mentioned in an earlier post, I recommend a visit to Jerome Rothenberg’s recent post presenting a selection of luminous “detached sentences” on the same subject by Ian Hamilton Finlay. Why, I wonder, did Finlay want to avoid calling these aphorisms? Maybe it’s just too pigeonholing a term.Read More

-

The Only Homeland

Asked to speak for 20 minutes in Vienna on the subject of “Literature and Exile,” Roberto Bolaño delivered a mordant speech that included this wonderful passage: Literature and exile, I think, are two sides of the same coin, our fate placed in the hands of chance. “I don’t have to leave my house to see the world,” says the Tao Te Ching, yet even when one doesn’t leave one’s house, exile and banishment make their presence felt from the start. Kafka’s oeuvre, the most illuminating and terrible (and also the humblest) of the twentieth century, proves this exhaustively.Read More

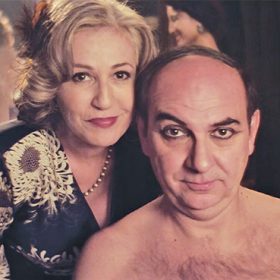

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.