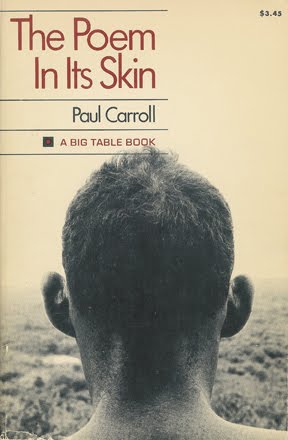

I mentioned Paul Carroll’s The Poem in Its Skin in the previous post but forgot to scan the cover. So here it is. I have to scan it because it’s out of print, along with all of the books from Carroll’s Follett Books imprint, Big Table Books. Via Big Table Carroll published the fat and important anthology The Young American Poets (1968), as well as the first collection of W. S. Merwin’s translations of Antonio Porchia, Voices, and Bill Knott‘s maiden volume The Naomi Poems, Book One: Corpse and Beans, attributed to Knott’s pseudonym “Saint Geraud,” whose dates on the title page are given as 1940-1966. (Luckily for us, Knott survived the demise of his alter-ego.) There is a good deal more to Carroll, of course, some of which is discussed in Paul Hoover’s memoir of his friend and mentor. Quite awhile back I quoted a poem of Carroll’s in the context of a post about Hokusai, but Perpetual Birders, I think, deserve to hear more from him. His finest poems are too long for me to wrestle with the HTML formatting, but here’s a shorter one that provides a taste:

Ode to Fellini on Interviewing Actors for a Forthcoming Film

Wasps and flowers fill the 1910 confession box.

Hot. Hot. But the lovely Witch of the North, wearing

a Puritan black velvet hat

a backless black bikini,

pedals slowly on her bicycle about the beach

at St. Tropez. Two Mercy nuns, whose fingers stink

like stale blue milk or Labrador,

herd us across the schoolyard

protected by the Swiss Guards of the snow;

we kneel, itching

inside snowsuits, wet, around the marble altar rail.

Monsignor floats in from the sacristy,

pressing a glass relic box against

his belly; we cry and kiss

the hairy knuckle of the virgin martyr. The hands

of Christ are the muscles of the sun:

they make flesh and bone from bread

and blood from ordinary

table wine. There is another moon,

its slow tides

the menstrual flow of the nuns. Around your office table

crowd an old alcoholic circus cloqwn,

a Christmas doll and three umbrellas

and Anita Ekberg’s mother

in a photo. Rain falls on artificial flowers. What

if everything comes from the sea? The angels

are ecstatic fish. Or helicopters.

And you, Fellini, are

a deep-sea diver, searching for the sex

of God. Good luck.

That’s from Carroll’s first collection, Odes (pictured in my previous post), like all his work, now out of print. It’s curious, I think, that no one with connections has stepped up to engineer a Collected Poems of Paul Carroll, via the University of California Press, for example. And it’s odd that Carroll has been utterly passed over by the maven of American poetic history, Ron Silliman, whose massive blog mentions Carroll only once—in a list of poets left out of Hayden Carruth’s anthology The Voice that Is Great Within Us; this although Carroll had a prominent place in Silliman’s Bible, Donald Allen’s The New American Poetry, 1945-1960. Well, Carroll was open to American poetry’s various tribes, but he was not a joiner—which may explain the eclipse in which his writing continues to languish.

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

Unfortunately, I'm one of those cranks who doesn't give a shit about whose work is important historically. That's an academic's game, and a parlor game at that. Anyone who thinks he knows who'll be considered a major American poet a century from now is self-deluded. All I can do is enjoy what I enjoy. Carroll is one of those I enjoy. His Fellini poem above, his ode to his

When I was at Iowa [1969-1972], Carroll was not discussed. I read The Poem in its Skin, and Odes, and found a straight-talking Midwesterner, who sounded more like a promoter and rabble-rouser than a serious poet. I understood that he'd inherited money, which made possible some of his publishing ventures. He'd married late, and had a late son (Luke). His fame seemed to rest on a brief