I want to celebrate the selection of W. S. Merwin for U.S. Poet Laureate. I encountered him first though his collection The Lice in a contemporary poetry class taught by James Doyle, and it’s still a touchstone book for me. Soon after that I stumbled on his great poem “Lemuel’s Blessing” in Paul Carroll‘s indispensable book The Poem in Its Skin (see below), and I was hooked. Merwin is one of maybe 20 poets I go back to when I get depressed over my own poetry or the poetry I’ve been reading. He is never far from the source, it seems to me, and he always reminds me (as a reader and a writer) what it feels like to touch that source. This selection is also a fine way of reminding everyone that the Poet Laureate is not a marketing position, but an honorary one. Merwin has honored the art in his own poetry and in his practice as a translator, so it’s fitting that we honor that irreplaceable contribution.

—–

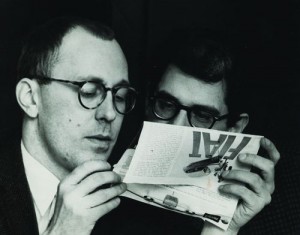

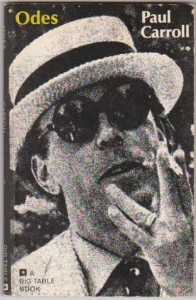

When I mentioned The Poem in Its Skin above I was suddenly aware that most Perpetual Birders will probably never have heard of it. It is essentially a collection of brilliant close readings by Paul Carroll of individual poems–the kind of thing poetry critics seldom bother with anymore, absorbed as they are in poetics, the increasingly arcane history of poetic schools, and the shoring up of declining reputations. Carroll was a poet (the above photo shows him with Allen Ginsberg) who did not seem to worry about such things. The Poem in Its Skin includes essays on Ashbery’s “Leaving the Atocha Station,” Creeley’s “The Wicker Basket,” Isabella Gardner’s “The Widow’s Yard,” Ginsberg’s “Wichita Vortex Sutra,” John Logan’s “A Century Piece for Poor Heine,” Merwin’s “Lemuel’s Blessing,” O’Hara’s “The Day Lady Died,” W. D. Snodgrass’s “April Inventory,” and James Wright’s “As I Step Over a Puddle at the End of Winter, I Think of an Ancient Chinese Governor.” The book concludes with an essay in which Carroll steps back from the individual poems and discusses each of the poets in context of what he calls “the Generation of 1962,” a year related not so much to birth dates as to the appearance of certain seminal collections of poetry. The very arrangement of the volume argues for the primacy of poems over poets, though Carroll doesn’t forget the fact that poets write poems from within the stream of history, and he shows how important that history can be.

Of course, close readings are out of fashion at the moment. I once remarked to a group of poets that I couldn’t find a single compelling poem in Alice Notley’s Selected, and was told that I needed to read all of her work in order to appreciate it. “The power is in the sequence, not in the individual poems.” It’s a way of reading poetry, I suppose, but it seems absurd to suggest that single poems don’t count. Carroll, who wrote some fantastic poems of his own, argues otherwise, and I’d challenge anyone to read The Poem in Its Skin side by side with, oh … let’s say Lyn Hejinian’s The Language of Inquiry, and see which approach honors poetry better. Obviously, my vote has already been cast.

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

I'll be talking on Paul Carroll and Isabella Gardner for the Inaugural conference of the European Beat Studies Network, see http://ebsn.eu/ Much information on their relationship is to be found in my biography of Gardner, for which I interviewed Carroll. The book is called Not at All What One Is Used To: The Life and Times of Isabella Gardner, see http://www.amazon.com/

Paul Carroll—Chicago Poet 1926-1996 <br />By Bob Boldt<br /> <br /><br />At North and Clyborn, I see you riding<br />west on that dilapidated bike,<br />your raincoat flapping.<br /><br />Only the North Avenue whores, awaiting <br />their harvest of Friday homebound drones, <br />regard you—indifferently.<br />Your shabby vestments promise nothing. <br /><br />The bobble-headed pigeons, <br />

I'm envious, Robert! Carroll is one of my heroes, really. His criticism enacted inquiries into poems in search of their inner substance, not to pass judgement or claim them for a cause. We could use more like him.

Hey Joe, <br />I appreciate both these recent posts about Paul Carroll. I studied under him in a course at the University of Illinois, Chicago, sitting across the table from Albie Goldbarth, who was also in the class, but who will never see these posts, I think, because he doesn't use a computer. <br /><br />Carroll was a good teacher as well as poet. He allowed each of us to do our thing and

Now that's a worthy fantasy! I have a couple of poets in mind myself who deserve the recognition. On the other hand, Merwin's example—as a poet, essayist, fabulist, translator, and independent scholar—is certainly worth spotlighting in this era of the academic poet. Not that all academic poets are compromised, but the system as a rule provides poor examples for young poets, sucking them

I'm happy to know about Paul Carroll and that book, The Poem In It's Skin (nice title, too), I'll scare up a copy soon I hope.<br /><br />I'm a big Merwin fan. I've always been attracted by the way he casts lines without punctuation. <br /><br />Still, I wish, when Merwin got the call from the Library of Congress, that he'd said something like, "You know I'm

I have to admit that part of my pleasure in Merwin's selection was the picture it brought to mind of Ron Silliman's head popping off like a champagne cork. And sure enough! I had a notion to reply to it, but I've had my say on the subject. And how does one reply to "What a distance we still have to travel"? <i>We?</i> Oh yes—he means the members of his tribe, much as George

Thanks for this post, as it brought back memories of Paul Carroll's book "The Poem in Its Skin" which I had in my library sometime, somewhere, someplace and which I now cannot find–what a loss! <br /><br />As for Merwin, compare your post to what <a href="http://Sillimanhttp://ronsilliman.blogspot.com/" rel="nofollow">Ron Silliman</a> has to say about Merwin's selection as the