I’ve never had the pleasure of meeting David Giannini face to face. We “met” a couple or three years back via this blog, when he emailed me a comment about some post or other, and I replied Our emails have continued to this day, sometimes in flurries, sometimes sporadically. From the beginning I was impressed by his intelligence, his wit, his commitment to poetry, and his generosity of spirit. As I’ve read his books one after another, I’ve also been impressed by his accomplishment. His work is solid through and through—no hollow effects, no inflated performance, but plenty of sophisticated music and plenty of humor. The more we corresponded and the more I read David’s work, the more curious I became about him. So some months back I asked if he’d be open to an interview, and after some of my usual dithering, questions and answers began winging their way between us. I trust you’ll enjoy the conversation.

* * *

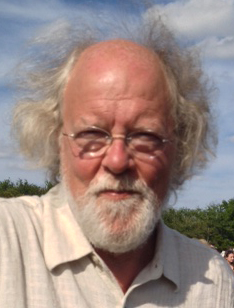

American poet David Giannini was born in New York City on March 19, 1948. His first book of poetry, Opens (1971), was published by Genesis: Grasp Press, which he edited and co-founded in 1967. He’s had numerous chapbooks and books published in the succeeding years. His most recently published collections of poetry include AZ TWO (Adastra Press,) a “Featured Book” in the 2009 Massachusetts Poetry Festival; INVERSE MIRROR, a collaboration with artist, Judith Koppel (Feral Press/Prehensile Pencil, 2012;) WHEN WE SAVOR WHAT IS SIMPLY THERE (Feral Press/Prehensile Pencil, 2013;) and RIM/WAVE (two full-length poetry collections in one book from Quale Press, 2012) SPAN of THREAD, a full-length collection of his prose poems is due out from Cervena Barva Press in 2015. His work appears in national and international literary magazines and anthologies. Awards include: Massachusetts Artists Fellowship Awards; The Osa and Lee Mays Award For Poetry; an award for prosepoetry from the University of Florida; and a 2009 Finalist Award from the Naugatuck Review. He has been a gravedigger; beekeeper; and taught at Williams College, The University of Massachusetts, and Berkshire Community College, as well as preschoolers and high school students, among others; and he worked as a psychiatric case manager for 31 years. His Installation, The International House Dust Collection, was exhibited most recently at the Yager Museum in Oneonta, New York. Giannini was the Lead Rehabilitation Counselor for Compass Center, which he co-founded, the first rehabilitation clubhouse for severely and chronically mentally ill adults in the northwest corner of Connecticut. He started Writers Read, an ongoing series of monthly readings by poets and fiction writers presenting at The Good Purpose Gallery in Lee, MA. He lives among trees in Becket, Massachusetts with his wife, Pam, and their two cats, Mina and Maya.

* * *

THE PERPETUAL BIRD: When you were a kid, what did you dream of being when you grew up? How did that work out?

DAVID GIANNINI: This is a difficult question for me! I dreamed of becoming so many things. At one point, very early on, I dreamed of becoming a praying mantis, a green alien thing like the one I discovered in a playground one day in first grade, then Mr. Potato Head, thanks to my aunt, Mickey’s, story-telling. Most of all, I dreamed of using my eyes and ears more, probably because my favorite uncle was an artist and my father was a musician and composer and we all lived in the same house with my Italian grandparents in New Jersey. As a kid poet, I learned to develop images and sounds based on family sounds and images. That’s one way things worked out for me, but not only because of dreaming, ha!

TPB: What did your parents dream you’d be when you grew up? How did they react to how things actually went?

GIANNINI: Both of my biological parents are dead. Since my biological mother abandoned me and my brother when I was three-and-a-half and he was six months old, she simply doesn’t figure into your question. My brother, as an infant, was sent to live “temporarily” with an uncle and aunt. My father and I went to live with my Italian grandparents and my uncle, Ugo, an artist, who was really a second father to me. At one point, my father thought I might follow in his footsteps as a musician, and he tried to teach me piano, and later I tried violin and then trombone, but I showed no talent or patience for playing instruments. He frequently mentioned that we all came from a family of autodidacts (although my father had studied at Julliard) and that “the only important thing is to be yourself.” My job was to become myself, whatever that meant. Later on, my dad enjoyed touting me as “the poet,” sometimes embarrassing me since I really had nothing much to show for my efforts. I was around 17 then, and already living on my own in Manhattan. I know that my father and, later, my stepmother worried about how I would make a living.

TPB: Seventeen and living on your own in Manhattan. (Sounds romantic to a guy who didn’t leave Colorado and environs until he was 22.) And now you’re … a “man of a certain age.” How have you gone about making a living during your journey from footloose 18 to your current presumably more rooted maturity?

GIANNINI: Back in NYC a friend and I managed to launch a magazine called Genesis : Grasp with funds generously provided by parents and grandparents, and to our surprise Andy Brown and Frances Steloff at Gotham Book Mart gave us a launch party. People as diverse as Andy Warhol and Richard Eberhart attended. James Laughlin of New Directions Publishing started publishing poems by me and my co-editor in his annual anthologies. We managed to publish the first four issues and a couple of supplements, all from donations and very few subscriptions, while again working in bookstores, scraping by. We sent a few gratis copies of our magazine to various English Departments in colleges around the country. The head of the English Dept. at Morris Harvey College in West Virginia responded enthusiastically and even paid to fly me and my wife at the time to the college, all expenses paid, so I could give a reading and provide a lecture on Gertrude Stein’s work in the auditorium there. It was filmed by Southern Educational Television. The college also gave me their Osa and Lee Award for a poem of mine. No one ever asked me about my formal schooling.

GIANNINI: Back in NYC a friend and I managed to launch a magazine called Genesis : Grasp with funds generously provided by parents and grandparents, and to our surprise Andy Brown and Frances Steloff at Gotham Book Mart gave us a launch party. People as diverse as Andy Warhol and Richard Eberhart attended. James Laughlin of New Directions Publishing started publishing poems by me and my co-editor in his annual anthologies. We managed to publish the first four issues and a couple of supplements, all from donations and very few subscriptions, while again working in bookstores, scraping by. We sent a few gratis copies of our magazine to various English Departments in colleges around the country. The head of the English Dept. at Morris Harvey College in West Virginia responded enthusiastically and even paid to fly me and my wife at the time to the college, all expenses paid, so I could give a reading and provide a lecture on Gertrude Stein’s work in the auditorium there. It was filmed by Southern Educational Television. The college also gave me their Osa and Lee Award for a poem of mine. No one ever asked me about my formal schooling.

Back in NYC, I couldn’t stomach living there any longer and had to move with my wife to New England. Even as a young child in East Orange , New Jersey, I would find a vacant lot as my favorite place to play and explore. There were black widow spiders and bees. I needed a sense of undeveloped nature, I mean desperately needed it. We wound up moving to Massachusetts in 1971, and I have now lived in that state for 44 years, never again in a city. So I went from living in Manhattan to living in a very rural mountain town where the only job I could find was to finish digging graves at the town cemetery and doing other manual labor chores for the town road crew. I had been building a publishing resume through the years, and eventually I applied for and obtained two large government grants and became a peripatetic poet-in-residence for several elementary schools. Because of my experiences and good reputation as a teacher in those schools, I was asked to teach a couple of poetry workshops at Williams College and later taught at various colleges in the state, including as a substitute one semester in James Tate’s MFA writing class at The University of Massachusetts. At one point I was short-listed for an honorary doctorate by faculty at North Adams State College (now the Massachusetts College for Liberal Arts in North Adams) for my work teaching graduating college seniors how to teach writing to elementary school students. I also worked through these years at other bookstores and on a small farm, plus homesteaded one year at R. G. Vliet’s house in VT, managing small livestock, beekeeping, and gardening.

After my divorce, and a second marriage and separation, one stepson died and I became increasingly drawn to work in the mental health field. I worked as a ground-level psychiatric caseworker for people with severe and chronic mental illnesses for the next 31 years, and eventually started several day programs for them in Connecticut. I still taught occasionally and at one point also had a business cleaning a movie theatre. These days I work only at home, and live with my wife Pam and our cats, all of us living happily in a house on a tertiary dirt road in Becket, MA.

TPB: Where and when did you begin to read poems for your own pleasure? What did it feel like—that early encounter? And …. where and when did you write your first poems? Who, if anyone, did you show them to?

GIANNINI: Before I answer more directly, let me say that in my book, Antonio & Clara, an extended prosepoem remembering my view as a seven year old ‘about’ my immigrant Italian grandparents with whom I grew up in East Orange, New Jersey, there are the following words: “Little sense but all sense was made with everyone talking at once, and the music of words, the music itself, the music danced!” I point that out because before I knew what Italian words meant I heard them musically on a daily basis, and there my first love of words was born, listening to a language known for its beauty, for its poetry. My father and uncle would sometimes quote a line from Leopardi or Shakespeare or Tagore, so then I had poetry in English and in translation. My Italian grandmother, Clara, was a retired opera singer who was, when I lived with her, almost completely blind, but she would occasionally boom arias across my ears while I sat in her black lap (she almost always wore black). Tosca. La Boheme. So there was always the pleasure of hearing words spoken musically or sung outright. It was thrilling, sometimes annoying, and almost always mysterious to listen this way, a practice that continues in me to this day! Later, oh, around third grade, there were all the Dr. Seuss books with their rhyming verses, and I wrote a little poem about snow that I showed to my in-school music teacher, who set it to music. My parents lost this to the wind over the years. I still remember the first two lines:

GIANNINI: Before I answer more directly, let me say that in my book, Antonio & Clara, an extended prosepoem remembering my view as a seven year old ‘about’ my immigrant Italian grandparents with whom I grew up in East Orange, New Jersey, there are the following words: “Little sense but all sense was made with everyone talking at once, and the music of words, the music itself, the music danced!” I point that out because before I knew what Italian words meant I heard them musically on a daily basis, and there my first love of words was born, listening to a language known for its beauty, for its poetry. My father and uncle would sometimes quote a line from Leopardi or Shakespeare or Tagore, so then I had poetry in English and in translation. My Italian grandmother, Clara, was a retired opera singer who was, when I lived with her, almost completely blind, but she would occasionally boom arias across my ears while I sat in her black lap (she almost always wore black). Tosca. La Boheme. So there was always the pleasure of hearing words spoken musically or sung outright. It was thrilling, sometimes annoying, and almost always mysterious to listen this way, a practice that continues in me to this day! Later, oh, around third grade, there were all the Dr. Seuss books with their rhyming verses, and I wrote a little poem about snow that I showed to my in-school music teacher, who set it to music. My parents lost this to the wind over the years. I still remember the first two lines:

When the snow sits on the ground

you can’t hear it, but it makes a sound.

Well, I didn’t really plunge into reading poetry seriously until high school when I met a transfer student from England who kept asking me, an avid reader, if I’d read The Coney Island of the Mind, The Happy Birthday of Death, and On the Road or other books by Beats, as well as “Tough Shit Eliot,” “Sam Mule Bucket,” et al., on and on. He leant me their books. Meanwhile, my father mentioned having seen and heard Dylan Thomas read in NYC. I began seriously reading Thomas as a singer-poet and also bad translations of haiku, and I was devouring more and more books in every imaginable field, but especially books of poetry, and I started trying to learn what made poems technically tick. To this day, Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet remains seminal to me. I sometimes felt that my already quite myopic eyes were bulging out because of so much reading! And since my friends were girls (with one exception) and in early high school I had a girlfriend, poetry and sex were always rolling around together. Well, they always do, no? I was writing the most awful drivel imaginable unless you were also a teen boy writing your own great lyric tripe without paying much attention to the difference between an erection and a lead pencil. That seems to have changed a bit over the years. Anyway, my girlfriend, whom I truly loved, loved the “poetry” I wrote, often for her. By age 20 I had a bonfire and burned all my very early manuscripts, and to this day, I don’t regret doing that. Ted Enslin once told me he did much the same, also without regret. I should also mention that I showed my writing, inflicted it, really, on my father and stepmother, who were usually supportive of my efforts. Also in high school, I wrote and tried to choreograph a ballet to be danced to Bartók’s Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta, and my girlfriend danced naked to it, privately, hence the reason for writing it in the first place.

TPB: Every poet, I imagine, has a personal pantheon. Assuming I’m right, list at least three members of yours and say something about why each is ensconced there.

GIANNINI: If my skull is the pantheon containing those poets illustriously dead to me, who are they and why do I sometimes walk upside-down inside my head trying to locate them? I’m not sure I can answer that latter part. “Who , if I shouted among the hierarchy of angels, would hear me?” asked Rilke.

GIANNINI: If my skull is the pantheon containing those poets illustriously dead to me, who are they and why do I sometimes walk upside-down inside my head trying to locate them? I’m not sure I can answer that latter part. “Who , if I shouted among the hierarchy of angels, would hear me?” asked Rilke.

The three that occur to me instantly are Shakespeare, Rilke, and Emily Dickinson. (I’m not touching on the moderns or post-moderns or contemporary poets.) I believe that for each of those three poetry was no mere subject to be studied, as in an MFA program, but a daily and natural event in their lives—language as it was living in and around them; and each shaped their occasions of poetry according to their developing vision or envisionings within experience. Each obtained a new angle, a way of seeing, under the sun, and that’s the best any artist can do, find her or his own angle and then “Tell all the truth, but tell it slant—.” [Emily Dickinson—TPB]

Okay, so those are my traditional and oldest members. They all sit in the same living room and sip tea. Thrones or the artifacts of worship are strictly forbidden. They were people. I have smaller chairs for Lorine Niedecker and George Oppen, Issa and Basho, Lao Tze and Tu Fu and Li Po, most of the Tang and other Asian poets. Lautréamont and Rimbaud (absinthe for them) are here in the living room— both were early “influences”; William Carlos Williams, e. e. cummings and Gertrude Stein and Laura Riding, Ponge and Char, and Mina Loy, James Wright, Merwin and Stafford and Snyder, as well as Creeley, Ted Enslin, and Cid Corman are all sitting around, too. So are Zbigniew Herbert and Trakl, et al.; various South Americans, too. The living chat with the dead and the dead reply with their own books.

But really, all one has read and experienced (reading well is also an experience) is “influence.” That’s obvious, I guess, but I really mean that I have no one influence, unless it was the remaining ear from my teddy bear, the ear I saw pinned to a clothesline moving by pulley outside a window of our apartment when I was three years old. I had cried and begged my parents not to throw away my careworn bear, and somehow I negotiated with them to wash and save the ear, a sort of pacifier at that point. Whose hands pinned the good ear and moved it into the sunlight? The ear was wet and of course soft and the lobe-less bottom of it flapped in the air, all that was left of that teddy. Yes, I would say that that ear, with all its reality/irreality and symbolic qualities, has had the most influence on me. A toy bear’s ear moving on a clothesline in the sunlight made enough juxtaposition to instill in me an early visual poetry before I knew that Poetry existed. The very sounds of words move on a line toward some type of light. And light may also be a type of ear. Well, I could go on, eh? To this day, when anyone mentions “having a good ear” (as applied to metrics or rhythmic clusters), I first see that ear at the top tier of my pantheon.

TPB: I mentioned Knausgaard’s My Struggle in a blog post, and you fired off a pithy email in reply: “Detailed excess always smells, whether Proust or Gnausgaard [sic]”. This hints at the planting of an aesthetic flag. Is it? And if so, what territory are you staking out?

GIANNINI: Nah! I flag no “aesthetics,” or better put: I have no aesthetic theory and don’t want one, ever. Such things usually consist of more detailed excess, with the accent on cess. It is very likely that Proust’s way wouldn’t exist without Gertrude Stein. I haven’t read more than a smidgen of Knausgaard, but I can’t help wondering if he, following Proust’s example, doesn’t also trace back to Stein. Hemingway does, too, but he learned the opposite of excess from Stein. He admitted that indebtedness to her, as I guess everybody knows. I simply have wide appreciation for a diversity of poets and for where poetry may be found, even with dust. Speaking of that, literal house dust led me to my International Dust Collection, a sort of hobby of mine, which led me to invent a new, if minor, form in poetry, one I call Tricollage; but you haven’t asked about that. Anyway, no aesthetics! What matters is to live into the poetry as it makes you making it. What most people don’t “get” is that what is found in poetry is only found there.

TPB: On December 29, 2014, the poet Alfred Corn posted this on Facebook:

What are the “poetics” of poems written in very short lines? Say, five or six syllables per, and sometimes only one syllable. I see a lot of poems like this that are, essentially, prose that has been shredded into little snippets. No doubt as a way to disguise the fact that what we really have is a prose text. So how do you make a good poem in brief lines?

So? How do you?

GIANNINI: Arrgh, such terms as “aesthetics” and “poetics” to me are not terms that are alive. They refer to unburied caskets without burp valves and therefore causing “exploding casket syndrome.” That’s something real, you know. Those terms come from too far up in the head, dead. Remember the book, The Joy of Sex? Well, a book about sex is not sex any more than essays or books on “poetics” / ”aesthetics” are poems. They can be fun to read sometimes, but they are always about the thing, not the thing itself, not the poem—person—at hand. As for broken prose passing for poetry, well—in the hands of a craftsman poetry can come of such endeavors. That’s not usually the case, but exceptions prove the rule. Cid [Corman] was a master at turning parts of letters or novels, even essays into poems. José García Villa did the same in the 1950s with his “Adaptations.” As for syllabics, well, sometimes they simply occur as one is writing; or else they are a deliberate technique (Cid, again, and famously Marianne Moore, for examples). Other times, the syllables are counted as in some versions of haiku. The very short poem or even poetic aphorism has to be caught, as Cid often said, as it is occurring.

I don’t quite believe in Fate, but there does seem something inevitable about the best poems, long or short. The best ones at least feel that way. Emerson in his essay on “Fate” speaks of it as “irresistible dictation.” That’s as good a definition as any for how a poem, if it is sincere, may come about. Very often a brief poem may be two or three lines culled from an otherwise failed draft. Many of my Aphoristics are intact lines from poems that seemed to have no other value. Many of Emily Dickinson’s first lines, like the one I mentioned earlier in this interview [“Tell all the truth, but tell it slant—”] are also aphorisms. Chicken or egg? Much of what I’ll call “broken prose syndrome” has come about since the 1960s and is largely due to the sheer proliferation of translated texts, which are almost inevitably prosy. Yes, I think that’s one, possibly the main, reason for such laxity in poems, for the lack of musical line. People reading translation after translation can come to think of the translations as primary texts. Anyone can see how that can lead to writing flat, broken prose and calling it poetry. Trouble is, it’s all more complicated than that. Why do we return to certain paragraphs in novels, say, if not because they are so beautifully written that they betray themselves and cross into poetry? I’m thinking just now of James Galvin’s novel The Meadow and of R. G. Vliet’s novels, also Paul Metcalf’s Genoa, or older fictions by Djuna Barnes, Kay Boyle, and Virginia Woolf. Lautréamont’s Maldoror and De Chirico’s Hebdomeros would be two others. On and on. And I haven’t even touched on the South Americans! I have a sort of prosepoem (sic) preface to my forthcoming book from Cervena Barva Press, Span of Thread, that begins like this: “Every poet’s an amateur on the way to the next word.” No matter what the individual poet thinks s/he has accomplished, before the unknown next word, s/he is a novice.

TPB: A poet like Corn would (evidently) dismiss your sequence “To the Wave, Poetry at Seacoasts” (collected in Rim/Wave [link here]). That sequence has to do with seeing and coasting, perception and intellect and a third quality I don’t have a good name for riding the waves … the ride (of course) depending on a certain resistance to those waves. It seems to me that’s how your short lines work in this sequence—as a way of resisting the ambient roar instead of yielding to it. It’s a fruitful tension, I think. Did you aim for anything close to this in your use of those short lines? Or am I suffering from a bad case of reading into?

Reprint edition of RIM/WAVE from Quale Press

GIANNINI: We all do and should have our biases, or we wouldn’t take a stance, we could not be artists [poets] or not very good ones. Corn has his slant in the same camp, I think, as James Merrill did, a Formalist camp, and as such I can’t expect him to accept as poetry the very short, even brief poems by others. If he doesn’t, then he leaves out a substantial list of poets all over the world. I would like to think that being inclusive is more valuable and humane than the seeming exclusivity of the New Formalists. If am wrong about the New Formalists’ general take on poetry, I’ll eat a tuxedo! They are, of course, the ones praised most by the most prominent critics. Let me quote Rilke here: “Works of art are of an infinite loneliness and with nothing so little to be reached as with criticism.” Amen! Okay, that said, let me get onto the two books of mine you mention, Rim and To the Wave (Rim/Wave for short). You may be “reading into” the Wave poems a bit, but I like that sense you get of “fruitful tension.” Every poem responds to good treatment. I had no deliberate plan for the book. It came to occur, be worked on, revised, over a number of years, out of my love of ocean and coasts. Several sections were published separately. Juliana Spahr of Leave Books first published the intact sequence, “Keys”; John Martone (tel-let press) first published “Seaphorisms”; and Mark Kuniya published “Low-Tide Cards” from his Country Valley Press. Although each of those “stand alone,” To the Wave is one work, whole, a complete book. Strange, but most people don’t “get” that a book may be written as a book, and not as smattering of little chiseled monuments, as so many anthology-pieces; so within the context of the whole book there is a good deal of lee-way for various rhythms, line lengths, aphorisms, and just plain notations. In each case, and the whole, I tried to see into some/thing, sea, seashell, person, etc., to reach an emotional-spiritual understanding. Most of the time this was not done by conscious effort, but as result of … well, just how I sense things. Some sections are more poetically musical, some are prose quotations from other writers, and yes, there’s even some “broken prose.” Does it really matter what we name the thing? It is a book.

I would like to think that readers feel into the work enough to sense my love for sea and land and the things of sea and land, even a sense of sfumato, as when the sound of the waves comes through fog—that hazy seaside sense of things in early morning, gull sounds coming in and out of the fog.

TPB: I love the notion that “every poet’s an amateur on the way to the next word.” You capture that richness of innovation in Rim (the first half of Rim/Wave) with its mix of poetry in lines, poetry in paragraphs, and quotations—an inner-life story. And yet on the back of the book there is this intriguing suggestion: “The book may be read alone or read aloud by at least two people.” I assume that’s your suggestion. Can you talk about the “voices” aspect of Rim and how the quotations work in relation to the rest of the text?

GIANNINI: Well, you ask about Rim itself, too, the other intact book within the covers of Rim/Wave. It is published by the wonderful press and publisher, Quale Press, Gian Lombardo’s press. Anyway, I first drafted Rim back in 1977-78. It went through at least 60 drafts. It wasn’t published until 20 years later, in a limited edition hardback from Indian Mountain Press! It was re-issued, duplicating the original, including woodcuts by Frank Feldman, by Lombardo in 2012, in paperback. So it is an “old” work of mine and my darkest one. It is a story, but more than that it is “an extended narrative prosepoem collage.” I wrote that because I didn’t know what the hell else to call this hybrid of narration that also includes broken prose, lines of poetry, and many quotes by other writers inserted into the text, both complementing and offsetting it. It is basically about an intelligent farm worker, his difficult life. It was produced once at The Becket (MA) Arts Center by Susan Dworkin using two actors for a theatrical reading, one actor reading the main narrative and the other reading the inserted texts. It is most effective read that way. It is meant to be read alone, too, of course, but the reader needs to be able to hold all the voices in her head at once. Several people have told me they like to read just the story and skip the insertions! But the insertions are what provide the larger dimensionality of the thing. It may be too difficult for me to speak further about it and make sense in an interview. Well, yes, that’s all I care to say about it now.

* * *

Check out these links to read some of David Giannini’s work online or to order copies of his books:

Prehensile Pencil Publications

* * *

[Read the second half of my interview with David Giannini here.]

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

[…] post concludes my interview with David Giannini. Jump back to Part One for a brief introduction and a substantial bio-/bibliography of the […]