There is no pleasure like a hot-spring bath. Ideally naked we slip into the steam and mineral cooking-egg smell of it, sliding bare buttocks down the slickly gnarled sloping rock until our chin rests on the amber surface of the water. If we pray, we pray to the forces of sacred nature, laughing and arguing as we might across the Thanksgiving table. We are part of their family.

I lied in that first sentence. Reading Stanley Moss is a hot-spring pleasure—an escape into healing intensities, words kneading the aches from intellect, feeling, and spirit. He teaches how to be a coherent self among other selves, an othered self, heroic and vital, yielding only under protest to ravenous time.

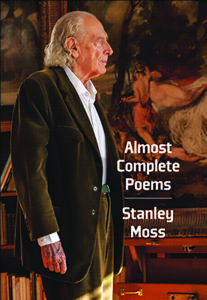

I say all this on the basis of reading his Almost Complete Poems. It is monumental (570 pages plus index), humanistic, various and new, old in the ways available only to the truly new. The magnetic north of his poetry is pleasure, its aim being to celebrate the holiness of desire and the desire for wholeness. There is no hot-and-cold, only the healing hot-spring heat that speaks from the depths of the earth.

Here’s a taste of Moss’s naked poetry….

~~~~

Hotel Room Birthday Party, Florence

Hotel Room Birthday Party, Florence

Mirror, mirror on the wall,

who’s that old guy in my room?

In the red nightshirt on my bed

I’m a kabuki extra. If I please

I can marry all

to nothing, snow to maple trees,

leap for joy over my head,

play bride and bridgegroom,

an old and young shadow on the wall.

I can play a decapitated head

laughing in its basket of flies.

There are no clocks in paradise,

a dog’s tail keeps time instead.

(Today be foolish for my sake.)

Which comes last, sunset or sunrise?

Nightfall or daybreak?

The day is Puccini’s,

the street is for madrigals,

the celebration in the cathedral:

a skull beside a loaf of bread,

but for my grandmother’s sake

it’s a portion of torta della nonna I take.

It is a double portion of everything I want.

A mirror is a stage: I’m all the comedies

of my father’s house and one of the tragedies.

I draw my boyhood face

in blood and charcoal

I hold my masks in place—

all the worse for wear

with a little spit behind the ear,

and because this is my birthday

like a donkey in its stall

let fall what may.

To be alive is not everything

but it is a very good beginning.

~~~~

February

to Arnold Cooper

A week ago my friend, a physician, phoned

to say he has lung cancer, “not much time

so come on over.” I brought him some borscht

I cooked and about a tablespoon of good cheer.

We kissed goodbye as usual.

Then it was as if

we walked out in deep snow.

He was still in bedroom slippers.

March was a long way off, the snow

much too deep for crocuses to push through.

Then it was as if he laughed,

“I lost a slipper. Poor snow.”

I put his bare foot in my woolen hat.

We talked about February and books

as if it were a summer day. I thought,

“No better mirror than an old friend.”

He said, “In my work I’ve done what I wanted to do.”

A branch broke off a sycamore, fell

into the snow for no reason.

The buildings of New York’s skyline seemed empty

of human beings, gigantic glass and steel gravestones.

These words are obsolete.

We had an early summer. He died the ninth of June,

directed toward eternity like a swan in flight,

Katherine and Melissa at either wing.

Surrounded by love, he landed in his garden—ashes now.

Hibiscus, roses, day lilies: hold firm!

~~~~

Jerusalem: Easter, Passover

The first days of April in the fields—

a congregation of nameless green,

those with delicate faces have come

and the thorn and thistle,

trees in purple bloom,

some lifting broken branches.

After a rain the true believers:

cacti surrounded by yellow flowers,

green harps and solitary scholars.

By late afternoon a nation of flowers: Taioun,

the bitter sexual smell of Israel,

with its Arabic name, the flower red clusters

they call Blood of the Maccabees,

the lilies of Saint Catherine, cool to touch,

beside a tree named The Killing Father,

with its thin red bark of testimony.

In the sand a face of rusted iron

has two missing eyes.

There are not flowers enough to tell,

over heavy electronic gear

under the Arab-Israeli moon,

the words of those who see in the Dome of the Rock

a footprint of the Prophet’s horse,

or hear the parallel reasoning

of King David’s psalms and harp,

or touch the empty tomb.

It is beyond a wheat field to tell

Christ performed two miracles: first he rose,

and then he convinced many that he rose.

For the roadside cornflower

that is only what it is,

it is too much to answer

why the world is so, or so, or other.

It is beyond the reach

or craft of flowers to name

the plagues visited on Egypt,

or to bloom into saying why

at the Passover table Jews discard

a drop of wine for each plague, not to drink

the full glass of their enemy’s suffering.

It is not enough to be carried off by the wind,

to feed the birds, and honey the bees.

On this bright Easter morning

smelling of Arab bread,

what if God simply changed his mind

and called out into the city,

“Thou shalt not kill,” and, like an angry father,

“I will not say it another time!”

They are praying too much in Jerusalem,

reading and praying beside street fires,

too much holy bread, leavened and unleavened,

the children kick a ball of fire,

play Islamic and Jewish games:

scissors cut paper, paper covers rock, rock breaks scissors.

I catch myself almost praying

for the first time in my life,

to a God I treat like a nettle

on my trouser cuff.

Let rock build houses,

writing cover paper, scissors cut suits.

The wind and sunlight commingle

with the walls of Jerusalem,

are worked and reworked, are lifted up,

have spirit, are written,

while stones I pick up in the field

at random have almost no spirit,

are not written.

Is happiness a red ribbon on a white horse,

or the black Arabian stallion

I saw tethered in the courtyard of the old city?

What a relief to see someone repair

an old frying pan with a hammer,

anvil and charcoal fire, a utensil worth keeping.

God, why not keep us? Make me useful.

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

Transcendent, Joe.––both Stanley Moss’s poems and the 199 words of your poetic prose that his words inspired.

Thanks for introducing me to this poet. I like his tone and the “touch” he gives every line.

That Jerusalem poem is breathtaking. Thanks Joe, for introducing us to this work.

All of Moss’s books are available online, either used or new. I’d recommend “The Intelligence of Clouds” as a good starting point. From there you can rove backward or forward and find all kinds of wonderful stuff.

Thanks! Don’t know if I can go the 570+ page distance right now, but I’m intrigued with what you shared.