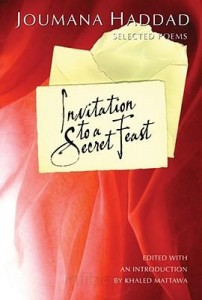

I bought the Lebanese poet Joumana Haddad‘s Invitation to a Secret Feast: Selected Poems for three reasons. First, the book’s title is beguiling; second, the selection is edited and partially translated by Khaled Mattawa, whose work as a poet and translator I’ve admired for some time; third, she is associated with the Shiir magazine group whose tutelary presence was Adonis (Ali Ahmad Sa’id), a man who in my humble opinion should have been awarded the Nobel Prize years ago.

Haddad defies every common American stereotype of Arabic women. Born in 1970 in Beirut, she speaks seven languages and works as a literary journalist for the daily Lebanese newspaper An Nahar and also teaches Italian. She is working on her Ph.D. in translation studies at the Sorbonne. And she’s writing a fiercely erotic, secularist poetry that draws on traditional Arab forms while reinventing and transcending them. I’ll give two examples, both of which convey the freshness and energy of her work, even in translation:

Haddad defies every common American stereotype of Arabic women. Born in 1970 in Beirut, she speaks seven languages and works as a literary journalist for the daily Lebanese newspaper An Nahar and also teaches Italian. She is working on her Ph.D. in translation studies at the Sorbonne. And she’s writing a fiercely erotic, secularist poetry that draws on traditional Arab forms while reinventing and transcending them. I’ll give two examples, both of which convey the freshness and energy of her work, even in translation:

Devil

When I sit before you, stranger,

I know how much time you’ll need

to bury the distance between us.

You are at the peak of your intelligence

and I am at the peak of my banquet.

You are deliberating how to begin flirting with me,

and I,

under the curtain of my seriousness,

am already done devouring you.*

I Am a Woman

No one can guess

what I say when I am silent,

who I see when I close my eyes,

how I am carried away when I am carried away,

what I search for when I reach out my hands.Nobody, nobody knows

when I am hungry, when I take a journey,

when I walk and when I am lost.

And nobody knows

that my going is a return

and my return is an abstention,

that my weakness is a mask

and my strength is a mask,

and that what is coming is a tempest.They think they know

so I let them,

and I happen.They put me in a cage so that

my freedom may be a gift from them,

and I’d have to thank them and obey.

But I am free before them, after them,

with them, without them.

I am free in my oppression, in my defeat

and my prison is what I want.

The key to the prison may be their tongue.

But their tongue is twisted around my desire’s fingers,

and my desire they can never command.I am a woman.

They think they own my freedom.

So I let them,

and I happen.

One of the most impressive qualities of Haddad’s poetry is how it creates complexity out of the simplest words. Except for a poem called “Adrenaline,” which is larded with scientific lingo, her poems are composed of everyday language, but collaged and layered, the meanings accumulated through morphing syntactical structures and dynamic rhythms. They stand out especially in an American context because our poems, bad and good, tend to reach for smaller effects, aspiring to be houses of mirrors rather than vistas seen from some windy precipice. Haddad insists on writing precipice poems—and what a pleasure it is to read them!

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

Hi, Brian. I was twitting myself a bit, since one of my collections is entitled <i>House of Mirrors</i>. I mean a confined space designed to look vaster and more complex than it really is; the complexity is all surface, a visual trick, and so is the apparent infinity of the place. A very subjective view of it, I'm sure!

Have a sense of what you mean by "precipice poems" but not so by<br />"houses of mirrors" poems.

Thanks for printing these poems. They are rich and layered, strong and supple. I'm glad to have had this introduction.