Readers of this blog know I’m a fan of openness. But defining “openness” is impossible: the very nature of it defies definition. And it’s easy to confuse it with “anything goes.” I once fell to arguing with a friend who insisted that anything an artist says is art is art; some poets have made the same assertion for their own writing. Can I be a fan of openness without sharing that assertion?

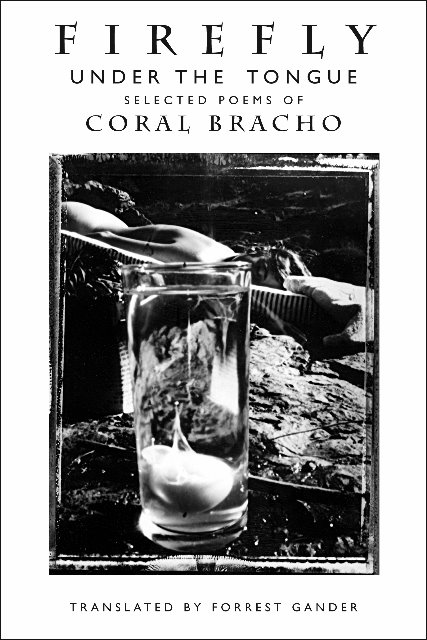

I guess it comes down to suggesting the kinds of openness I’m actually a fan of. Let me start with a remarkable Mexican poet, Coral Bracho, whose selected poems, Firefly Under the Tongue, is now available from New Directions, admirably translated by Forrest Gander.

Bracho’s poetry operates on several levels at once; all poetry does, of course, but in most poems the central energy pulses beneath a relatively clear surface: a narrative, explicit or implicit; an intelligible sequence of images and sounds; a coherent pattern. Such poems provide a surface that contains or translates the leviathan mysteries that thrive in the depths, and readers view them from a distance.

Bracho’s poetry operates on several levels at once; all poetry does, of course, but in most poems the central energy pulses beneath a relatively clear surface: a narrative, explicit or implicit; an intelligible sequence of images and sounds; a coherent pattern. Such poems provide a surface that contains or translates the leviathan mysteries that thrive in the depths, and readers view them from a distance.

The openness of Bracho’s poetry lies in its willingness to throw her readers overboard and make them swim. There are no easily graspable flotation devices. We’re tossed along on a sometimes confusing surface and can feel the leviathans brushing our feet. These are not poems that turn into lifeboats if one can only find the inflation cord. And Bracho doesn’t trivialize our efforts in the way Ashbery, for example, too often does; her poems are always about something, and are therefore intellectually and spiritually compelling.

Bracho’s openness reminds me of Bonnefoy‘s, but it’s not as remote; it reminds me of Vallejo, but its not so manic, so despairing; it reminds me also of Rilke without the spiritual rhetoric, of Paz without his sometimes overactive circularities, and of Hopkins without his thorny cadences. Bracho gives the impression of clarity without overly defined details, so she also reminds me of Van Gogh.

Here’s one way of looking at the openness I mean, through the lens of two difference translations of her poem “Poblaciones lejanas.” Let me point out that the title itself hints at the openness I admire. “Poblaciones” literally means “populations,” hence “Distant populations”; but the “poblaciones” also means cities or towns, for which there are perfectly straightforward Spanish terms—ciudades and pueblos respectively. Bracho wants us to understand these “distant cities” as something more than architecture, as loci of interpenetration, where humanity and architecture exist symbiotically.

Anyway, the first translation is by Forrest Gander, and it’s frankly wonderful. The second is mine, and I won’t characterize it except to say that I believe every meaning in it exists in the Spanish as surely as the meanings in Gander’s version exist there. And there are more that I could find no way to bring over into English! Translation always involves choices, of course, but Bracho makes those choices especially painful. Which is why I imagine she’ll attract all sorts of translators in the future, just as Neruda and Rilke have—and for the same reasons.

POBLACIONES LEJANAS

Sus relieves candentes, sus pasajes, son un salmo

luctuoso y monocorde;

los niños corren y gritan,

como pequeños lapsos, en un eterno, enmudecido

sepia demente. Hay ciudades, también,

que dulcifican la luz del sol;

En sus espejos de oro crepuscular las aguas abren y encienden

cercos de aromas y caricias rituales; en sus baños:

las risas, las paredes reverdecientes;

—Sus templos beben del mar.Vagos lindes desiertos (Las caravanas, los venavales, las noches

combas y despobladas, las tardes lentes,

son arenas franqueables que las separan) mirajes, ecos que las

enturbian,

que las empalman;

un gusto líquido a sal en las furtivas comisuras;

Y esta evocada resonancia.DISTANT CITIES

Their incandescent reliefs, their passages, they are

a mournful, single-chorded psalm

the children run squalling

like tiny slips in an endless, hushed

and distracted sepia. There are also cities

that sweeten sunlight;

In their mirrors of golden gloaming, waters unfold and ignite

pockets of aroma and ritual caresses; in their baths:

laughter, the greening walls;

—Their temples sip from the ocean.Lovely deserted boundaries (The caravans, foehns, the bulging

unmanned nights, heavy afternoons,

it is loose sand that holds them apart) mirages, echoes that

cloud them,

that bind them together;

a liquid taste for salt in the furtive corners;

And this triggered echo.—Coral Bracho, tr. by Forrest Gander, from Firefly Under

the Tongue: Selected Poems of Coral Bracho***

REMOTE POPULATIONS

Their white-hot reliefs, their passings, are a psalm

mournful and monotonous;

the children race about and shout,

like small lapses, in an everlasting, muted

cloud of demented cuttlefish ink. There are cities

also that soften sunlight:

In their mirrors of twilit gold, the waters open and inflame

enclosures of scents and ritual caresses; in their bathrooms:

laughter, the reawakened walls;

—Their temples drink from the sea.Blurred abandoned boundaries (The caravans, the sciroccos, the

warped and dissociated nights, the sluggish afternoons,

are scattered sands that separate them) loomings, echoes that

confound them,

that connect them;

a mouthwatering taste of salt in the furtive commissures;

And this conjured resonance.—Coral Bracho, tr. by JH, just for fun

As you can see, I could simply not let go of Bracho’s “comisuras” in the penultimate line—a word that Gander correctly renders as “corners,” but which also means “joints” (as between two bones), “seams” (as in the seam where upper and lower eyelids or lips meet), “bands” (as in the bands of nerve tissue connecting the hemispheres of the brain or the two sides of the spinal cord), and “suture” (as in the row of stitches holding together the edges of a wound or surgical incision). This kind of openness, which involves the intelligent deployment of multiple meanings that all “more or less” work together, is one quality that makes Bracho’s poetry so involving.

Click here to hear a fascinating radio interview with Bracho and Gander on KCRW 89.9 FM, “Southern California’s leading National Public Radio (NPR) affiliate.”

****

UPDATE: I kept worrying about that cuttlefish! “Sepia” is cuttlefish, but I’ve come to suspect that Bracho means cuttlefish ink: the brownish-black substance squirted by a cuttlefish in self-defense. (This seems more in accord with the drift of the poem.) Hence, my old lines:

the children run about and shout—

like minuscule errors—in an everlasting, suffocated

and crazed cuttlefish. There are cities . . .

now read:

the children race about and shout,

like small lapses, in an everlasting, muted

cloud of demented cuttlefish ink. There are cities . . .

Well, it makes better sense to me, at least!

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.