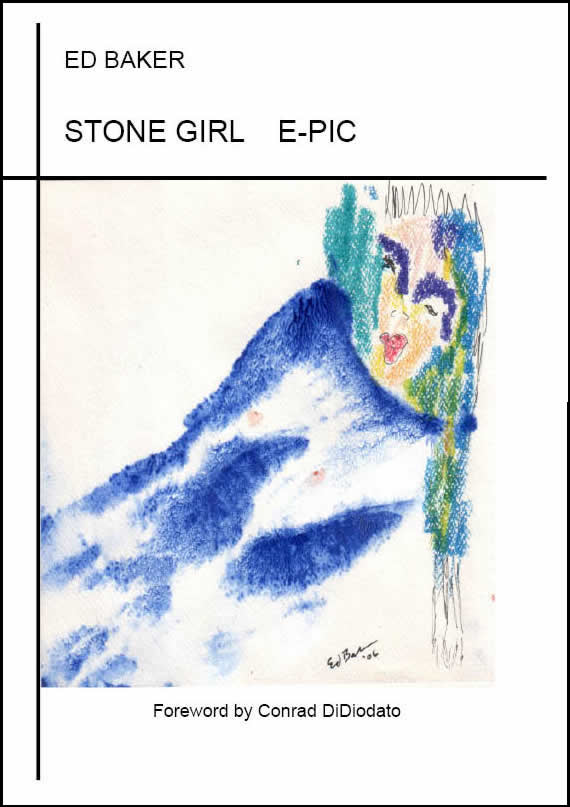

I’ve been struggling—let me admit it—to find a way to write about Ed Baker’s Stone Girl E-Pic. It’s a 515-page poetic adventure, the reading of which is like watching sparks thrown off by a fire: the fire’s below the rim of the firepit, so you can’t see it directly, but the climbing sparks, the waves of light and heat under a skyful of stars—this is the sensation Stone Girl produces.

The book is divided into five volumes of unequal length (162, 36, 23, 11, and 283 pages respectively—though don’t rely on my math!) that explore the relationship between two figures called Walking Mind and Stone Girl. It’s a Taoist relationship—the classical

Yang/Yin, masculine/feminine

inter-relationship grounded in eros. (Taoism’s

Five Agents may illuminate the five-part structure of the book as well). My guess is that the

E-Pic of the title gestures toward “Erotic Picture” as well as toward the root word of “epic,”

epos—“word, song”. The arc of energy between

epos and

eros, that is

the interrelationship of the two, is the energy that drives Baker’s poetry. (Not just in

Stone Girl, either—but that’s a thread I can’t follow here.) What makes the poetry so vibrant is that Baker presents this energy as it appears in a variety of traditions (philosophical and poetic), situations (cosmic and personal), and forms (poems in sequence, poems with drawings, poems

in drawings, drawings alone, and in volume 5—poems alone). Pound said that an epic is “a poem including history,” but Baker’s e-pic is mercifully free of history in the Poundian sense. It is, in a way, a fiercely anti-Poundian poem (more on that below).

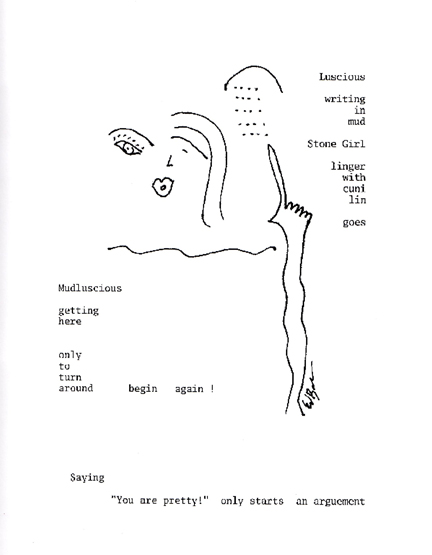

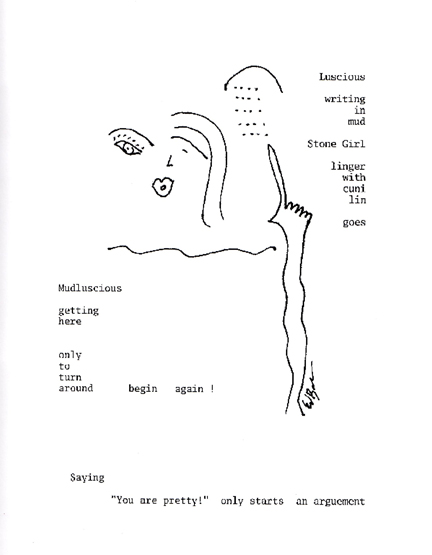

There is nothing programmatic about all this: Baker writes with evident spontaneity, discovering and layering as he goes. The method he has developed to register this process is what he calls “blown language,” meaning (I’m sure) “blown” in its multiple senses: “moved by wind,” “breath expelled through pursed lips,” “sent flying,” “in a state of flowering”. Often enough these senses are active in a single poem or movement of poems. Here’s an example from volume one:

On a single page we have a resonance composed (composted?) of vibrations from

Picasso;

e. e. cummings (“In Just- / spring when the world is mud- / luscious…”); the complex punning on “cunnilingus” (

cunnus “vulva” +

lingere “lick”—but the

lingere here interrupted or forestalled), which according to

Webster’s Online Dictionary “is accorded a revered place in Chinese Taoism” (the sex act, I mean, not the punning!); and perhaps an echo of Joyce’s

Wake, at the cycle’s end: “Finn, again!” Baker leaves plenty of room for the reader to invest his or her own experience, make his or her own connections—and that openness is one of the great pleasures

Stone Girl has to offer.

The danger of such writing, of course, is that the reader will feel chronically unmoored, lost in wordplay or arcane references. I can’t pretend that I wasn’t puzzled now and then—or maybe “bemused” would be a better word.

Stone Girl frequently requires any reader who doesn’t happen to be Ed Baker to consult a dictionary, encyclopedia or other source (as I had to with the word

kalpas in the excerpt quoted next below); sometimes it requires an educated (or half- or un-educated) guess. But the book challenges without rubbing the reader’s nose in his or her ignorance, the way a less open writer—

Geoffrey Hill, for example, a veritable control-freak of a poet—is pleased to do. The openness of

Stone Girl inspires engagement, I mean, and that is all to the good.

Still, I supposed it’s fair to ask what a 515-page book is finally about. Let me take a stab at that question.

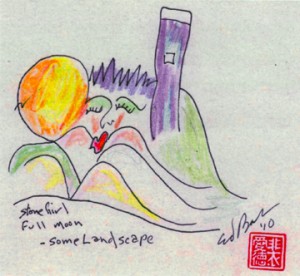

First, on the narrative level, we have a man and a woman, evidently a younger woman; the man has fallen in love with the woman, but she is married and has a child. As the book goes on, she discovers she is pregnant. Although she doesn’t love her husband, she has a duty to her children (born and unborn) to keep the family intact, and in the end has the child and remains with her husband. This is the slender throughline that Baker counts on to help his book cohere. And it works. Now and then we wish to know more (we are still in the Age of Oprah, though Oprah herself has moved on), but most of the time the progress (or non-) of the narrative doesn’t matter. Why not? For one thing, because the narrative enacts an internal process by which Walking Mind discovers the Stone Girl

within himself; the story, that is, amounts to an initiation that ends with the fulfillment of the self-discovery process. Secondly, instead of curiously, even pruriently,

observing this love affair (if it’s right to call it that), we participate in the initiation; this happens because we’ve been gathered up into Baker’s “blown language”—

into the moments that his method forces us to slow down and enter deeply.

Let me try to massage my HTML to give a couple of glimpses of Baker’s approach in words-alone. The first passage is Williamsesque:

walking mind

sitting on

outcrop

stone girl

blowing

anemones

to say

how far we

have moved

say it so

stumps

in

back

yard

watch

wait

cultivation

precipitates

rot ting

what is hurry up for worms

instead of

pointing to

head

point into

mind

where mind is

heart is

let

go

of

it

it is not so

easy

all of

these

countless

kalpas

writing

love

poems

to a

stubborn rock

The second passage is quite different—more “blown,” it seems to me:

moon drift

does

not

deter

moving

child

thinking

she

is

a cloud

did mind write this

oh bang

mind

fluttering

swaying

tablet

her

h i p s

lah – la – la – lah – lah – la

hao bo moon

layering

beats

drum

mind

stone

butter fly heart

beating

beating

being

The gift of Baker’s method is that it releases the hidden energies of connotation, etymology, allusion, and syntax—as in Joyce, not haphazardly, but with a focus that is clear-eyed, i.e. “realistic”. Joyce famously said of the interior monologue method he used in Ulysses that “it hardly matters whether the technique is ‘veracious’ or not; it has served me as a bridge over which to march my eighteen episodes.” Is Baker’s “blown language” a technical advance that others can adopt, as so many fiction writers tried to adopt Joyce’s interior monologue? I tend to think not. Like Joyce’s dream-lingo in Finnegans Wake or the acrobatic typography of e. e. cummings (who, like Baker, was both a poet and a visual artist), it is inimitable. Baker himself may continue to explore it, but in anyone else’s hands it would seem derivative.

There is another aspect to Baker’s work—the deeper aspect—that is also akin to Joyce. It is devotional, and the object of its devotion is the Goddess. Ultimately, Stone Girl is a Goddess figure, what Goethe called “The Eternal Feminine” (in the last lines of Faust: “All that is perishable is but an allegory; / The Eternal Feminine draws us on”). Cummings—the other writer I hear most in Baker’s work—was also devoted to the Feminine, but oddly enough in a conventionally Romantic way. There are simply more

ideas in Baker’s poetry than in cummings’, more concern for the Real; which is why, in the end, I think of

Stone Girl as devotional in the complex Joycean way. The psychic (I would say “spiritual” but it’s too loaded a term) energy that flows through Baker’s lines (written and drawn) light up every level of the work, so that one’s first impulse upon finishing it is to go back to the beginning and start reading again.

I should add that Stone Girl has a terrific preface by Conrad DiDiodato, which does a much better job than I can do of placing Baker’s poetics in a historical context. I won’t reprise his insights here. But I do want to return to my earlier point that Stone Girl is “anti-Poundian,” which has something to do with situation Baker’s poetics within the Modernist tradition. Whereas Pound cooked up a stew of which, in Canto 116, he wrote “I cannot make it cohere” (note the implicit reliance on will in that line), Baker yields to the outer/inner motion—narrative and contemplation—and allows it to shape his language; whereas Pound builds a static collage of images and allusions, Baker tracks a single, albeit wandering, motion—an approach that makes Stone Girl feel open and involving, as opposed to The Cantos, which (for me, at least) are closed and aloof. Small wonder that Basil Bunting compared The Cantos to the Alps: massive, complex, loftily beautiful—and frozen. Baker, by contrast, immerses us in the flow of thought/emotion/insight that arises from the Walking Mind/Stone Girl relationship. I’m sure the old boy from Idaho wouldn’t know what to make of it….

There are, of course, other writers whose influence seems to course through Stone Girl: William Carlos Williams, Cid Corman, John Martone, Carl Jung, Marija Gimbutas, and Lorine Niedecker to name a few; but I don’t want to go too far down that road. The question of influence can all too easily distract us from the work itself, which in this case deserves—and rewards—our singular attention.

___________

**UPDATE**

Note Conrad DiDiodato’s pre-publication take on the first 20 pages of Stone Girl here.

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

This comment has been removed by the author.

for those who are yet<br />following this<br />here is link to John Mingay's review :<br /><br />http://www.scribd.com/doc/234402440/Stone-Girl-E-pic-Review-by-John-Mingay

HEY JOE ! She is back in the "most popular" list….<br /><br />JEESH ! <br />what does this mean ?<br />what does anything ?<br /><br />John Mingay also has a nice review/read/take re: Stone Girl…<br />(and it is on the net…. and on my Scribd "stash"…<br /><br />he titles his review something like : "Love is Everyday Actions"…<br />which is a say right out

And you,<br />Vassilis!

Joe,<br /><br />good<br /><br />for you, good<br />for Con<br /><br />rad, good for<br />Ed, good<br /><br />for all of us–<br />thank goodness<br /><br />for you.

This comment has been removed by the author.

Mr. Natural ?<br /><br />NAUGH ! He's the crazy one. I'm the sane one who just pretends to be crazy<br /><br />in order to maintain my sanity<br /><br />well..<br /><br />keep on truckin get in you bag and do your thing<br />and above al:<br /> keep on keepin on<br /><br /><br />K.

Conrad: I fretted over what you'd think of it, because I value your opinion and was vividly aware that almost everything I wrote could stand a good deal of development. I've been using those little colored Post-It markers when I'm reading something for review, ergo my copy of <i>Stone Girl</i> is bristling with them—red, blue, yellow, orange, green—like some exotic jungle bird. There

WOWOW !<br /><br />thanks Joe… your read of/ take-away of<br />this review<br /> has taken my me far beyond<br />of what I was consciously/aware of when in the<br />(process of) the doing<br /><br />and<br />as I re:call<br /><br />your down-line "stuff" was a bit differently as on my pages onebyonebyone<br />

I was pleased to write it, Alan, but frustrated that I could only suggest the scope and effect of Ed's work. I regret (sort of) grinding a couple of my own axes in the piece, but significant poetry forces the reader to place it in context and then assess both the poetry and the context itself. Ed's poetry forces one to rethink the modernist project, it seems to me. I wish I could have

Joseph,<br /><br />outstanding review of Ed's work. The intersections with Joyce & cummings, as well as the Taoist touches, are illuminating. As any reader of Ed Baker knows, STONE GIRL E-PIC is a rich but luxuriantly wild text of scaling trees, rhizomes and dropping vines, no one of which alone will give you the true garden.<br /><br />Thank you!

Thank you for this insightful and considered review of Ed's work. He is a unique writer who deserves wider attention, and I'll be publicising your review as widely as I can. Best wishes, Alan Baker (no relation to Ed), Editor, Leafe Press.

This comment has been removed by the author.