When I was a kid a dentist told me I would never have to wear braces. “Your teeth will never get too crowded in your mouth,” he explained. “You have a simian jaw.”

I know. Ha ha. Monkey boy.

But the truth is that humans and a species of monkey called the macaque (according to an article on LiveScience.com) “share about 93 percent of their DNA. […] By comparison, humans and chimpanzees share about 98 to 99 percent of their DNA.” In other words, we all have some kind of simian jaw. And if there is a God, it/she/he made us not out of clay but out of monkey matter.

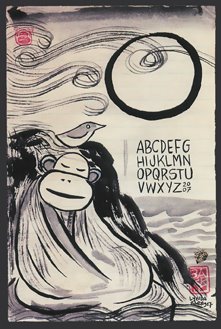

All this is to explain why I’m posting a drawing by Lynda Barry, which appears in the Summer 2008 issue of Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

“I paint these monkeys with a brush and hand-ground Chinese ink,” she writes in the accompanying article. “I found the paintbrush when I was working on my novel Cruddy, getting nowhere because I was trying to write it on a computer. The problem with writing on a computer was that I could delete anything I felt unsure about. This meant that a sentence was gone before I even had a chance to see what it was trying to become.” She goes on to explain how forgoing the computer in favor of writing her book with a brush “allow[ed] the unexpected to grow. I finished my novel.”

Anyone who’s heard me rant against composing poetry on a computer will understand my appreciation for Barry’s stance.

Not that Barry’s a Luddite. It’s just that she appreciates the two-milennia long tradition in which “brush, ink, and Buddhism are all bound together.” (Clearly this is the key insight that earned her a place in Tricycle.) What’s more, she ends with an observation that works for artists and writers alike, I think—even those of us who don’t write with brushes.

“The picture you make is not so important. Move your brush not to make a picture, but make a picture in order to move your brush.”

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

Thanks for this though-provoking post, Joseph, from one with too many teeth in a still simian jaw!