I’m posting this two days late because the calendar and I have been on the outs lately, both work and personal deadlines slipping like fish through the pirate-skeleton’s bony fingers….

|

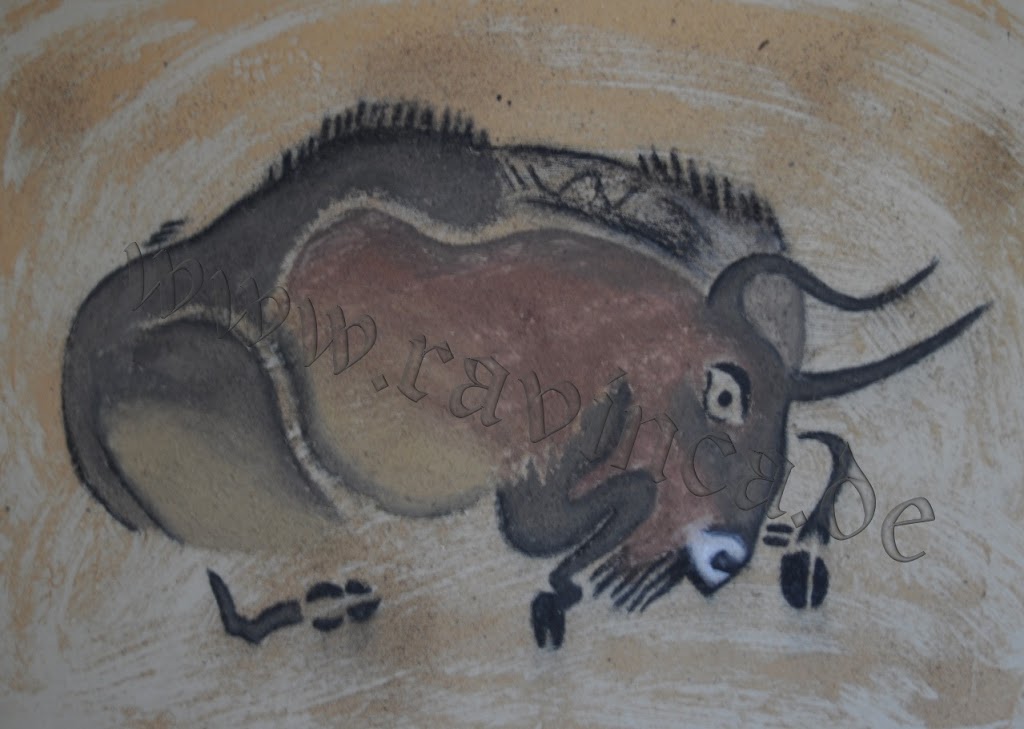

| A detail from Lascaux. The photographer’s watermark does not date from the paleolithic. |

The following passages are drawn from Clayton Eshleman’s Juniper Fuse: Upper Paleolithic Imagination & the Construction of the Underworld. I’ve never developed a liking for Eshleman’s poetry, which takes up much of this book, but the prose sections are illuminating:

Poetry twists toward the unknown and seeks to realize something beyond the poet’s initial awareness. What it seeks to know might be described as the unlimited interiority of its initial impulse. If a “last line,” or “conclusion,” occurs to me upon starting to write, I have learned to put it in immediately, so it does not hang before me, a lure, forcing the writing to skew itself in order that this “last line” continues to make sense as such.

*

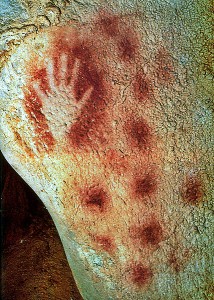

From the Pcch Merle cave—a handprint between

18,000 and 27,000 years old

It is possible to formulate a perspective that offers a life continuity, from lower life forms, through human biology and sexuality, to the earliest imagings of our situation, which now seems to be bio-tragically connected with our having separated ourselves out of the animal-hominid world in order to pursue that catastrophic miracle called consciousness.

*

Concerning witches, Hans Peter Duerr writes:

As late as the Middle Ages, the witch was still the hagazussa, a being that sat on the Hag, the fence, which passed behind the gardens and separated the village from the wilderness. She was a being who participated in both worlds. As we might say today, she was semi-demonic. In time, however, she lost her double features and evolved more and more into a representative of what was being expelled from culture, only to return, distorted, in the night.

[Neither Duerr (apparently) nor Eshleman unpack this tantalizing notion. It strikes me that eventually the “hag” (fence) rail was transformed into the witch’s broomstick—a compensation for the repression of energies deemed negative or “demonic” by the dominant culture. As with all compensation, the repressed element gains power: in this case, repression liberates the witch from the border between village and wilderness, and she is therefore free to invade the village, bringing the “wild” right into the villagers’ tidy homes.—JH]

*

I continue to feel that while the cave environment was extremely conducive to trance, something in daily and nightly life had to encourage certain people to go into the caves on a quest. That is, there must have been a crisis outside the caves that some people felt could only be resolved inside them. In my thinking, given the materials we have to work with, a resolution involved the momentary reestablishment of a human and animal connection, that to be reestablished had to have been lost, or sensed as being lost. I have proposed that this loss, or separation from animals, which was occurring during the Upper Paleolithic, may account for animals being put on walls as projections of the animality Cro-Magnon people were distancing themselves from. The fact that realistically depicted animals are present but not part of any realistic, survival-based landscape is very odd, and strong suggests that while the animal outlines depend on accurate observation, they appear on walls as psychological entities.

*

Horses are very popular animal helpers in historic shamanism, and are employed in many contexts. The Norse Odin, for example, who displays many shamanic aspects (such as changing shape at will into a bird, beast, fish,. or dragon, evoking the Greek Proteus), rides an eight-legged horse. Sleipnir, who is, according to [Mircea] Eliade, “the shamanic horse par excellence.” Horses enable shamans to make mystical journeys and to fly; they carry shamans, gods and the deceased into the beyond.

[This passage struck me because it carried me back to a haunting poem by Tomas Tranströmer, which goes like this:

THE OPEN WINDOW

(tr. Robert Bly)I shaved one morning standing

by the open window

on the second story.

Switched on the razor.

It started to hum.

A heavier and heavier whirr.

Grew to a roar.

Grew to a helicopter.

And a voice—the pilot’s—pierced

the noise, shouting:

“Keep your eyes open!

You’re seeing this for the last time!”

Rose.

Floated low over the summer.

The small things I love, have they any weight?

So many dialects of green.

And especially the red of housewalls.

Beetles glittered in the dung, in the sun.

Cellars pulled up by the roots

sailed through the air.

Industry.

Printing presses crawled along.

People at that instant

were the only things motionless.

They observed the their moment of silence.

And the dead in the churchyard especially

held still

like those who posed in the infancy of the camera.

Fly low!

I didn’t know which way

to turn my head—

my sight was divided

like a horse’s.Those last lines—“my sight was divided / like a horse’s”—suggest that Tranströmer is tapping into shamanic consciousness. —JH]

I wish I could say that I have something of my own to share, but gainful work used up all my energies this past week. I could read and underline and scribble marginalia—but my muse seems to have gone off somewhere to sulk.

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

This comment has been removed by the author.