This article appeared in the March/April 2009 Issue of Contango Magazine. ©2009 by Joseph Hutchison.

I’m posting it as a way offering up a strange idea: the notion that art, including poetry, should be useful. Exactly how is debatable, of course, but the awareness of use that informs Jim Bednar’s approach to his art is something I’d like to find an analog for in poetry.

**********

“Between Hunger & Dream”: The Artistic Journey of Jim Bednar

The Story in a Nutshell

Let’s say that a young man, very young, falls in love. Not with a woman (another story), but with a craft. The craft is ancient, difficult to learn, and tough to make a living at; it’s also seductive, attractively complex. He’s enthralled, even obsessed. But over time he becomes disillusioned, not so much by the craft as by the situation in which he must work, and in the end that disillusion poisons the craft itself. In the end he walks away from the craft in order to re-center himself and regain a sense of balance.

For years he wants nothing to do with the craft. Besides, life happens in ways that make the craft impossible for him.

Then one day there’s a chance encounter, a phone call, a series of unexpected events—and suddenly it’s back, the old craft-urge, that original “fire in the belly.” He takes the craft up again, and this time his whole world realigns around it. He finds himself resituated, finds that the painful, unfinished business of the past has become understandable, expressible-even forgivable. It’s like a dream. Everything starts falling into place.

Full Disclosure

I can’t be objective about Jim because he and I go way back. All the way to seventh grade at Denver’s Skinner Junior High, where he used to crush me at intramural basketball. We shared various enthusiasms—John Mayall and the Blues Breakers, the poetry of Gary Snyder, the Zen essays of D. T. Suzuki—and we each wrote poetry that the other critiqued. Jim also shared his passion for shaping clay, but he could not share his talent for it-at least with me. I battered a few spinning lumps while he raised his eyebrows at me, but that was it. I lived (still do) too much in my head; between poetry and pottery, Jim managed to find a middle way. I remember envying his balance.

Love at First Sight

Jim Bednar was 21 when he started working with clay. The impetus came from wandering into an art class at Knox College, in Galesburg, Illinois, where he was majoring in History and writing poems for the pure pleasure of it. The noise of the kiln, the smell of the clay, and the student pottery on display grabbed his attention. Call it love at first sight. Then the Knox History program lost its accreditation, and Jim—unwilling to take on the extra coursework and attendant expenses that would be required to graduate—dropped out, returned to his welcoming parents’ home in Denver, and started working construction. He also joined a pottery class at Castle Clay, a potters’ organization that’s still active in the Denver area, and began soaking up the guidance of other potters. When asked who the most influential potter was, Jim says, “There were three. Nancy d’Estang. Nancy d’Estang. And Nancy d’Estang.” A master potter and former student of renowned ceramic artist Warren MacKenzie, d’Estang worked in Denver until the mid-1980s and is now based in Connecticut.

Jim Bednar was 21 when he started working with clay. The impetus came from wandering into an art class at Knox College, in Galesburg, Illinois, where he was majoring in History and writing poems for the pure pleasure of it. The noise of the kiln, the smell of the clay, and the student pottery on display grabbed his attention. Call it love at first sight. Then the Knox History program lost its accreditation, and Jim—unwilling to take on the extra coursework and attendant expenses that would be required to graduate—dropped out, returned to his welcoming parents’ home in Denver, and started working construction. He also joined a pottery class at Castle Clay, a potters’ organization that’s still active in the Denver area, and began soaking up the guidance of other potters. When asked who the most influential potter was, Jim says, “There were three. Nancy d’Estang. Nancy d’Estang. And Nancy d’Estang.” A master potter and former student of renowned ceramic artist Warren MacKenzie, d’Estang worked in Denver until the mid-1980s and is now based in Connecticut.

In those days Castle Clay was suffering growing pains, and important jobs needed doing for which nobody else was willing to step up. Jim took it all on, calling on his recent construction experience and the happy blindness that is the great gift of youth. He mastered the crucial, tedious, and hazardous process of mixing clay; learned the delicate process of stacking pots in the kiln so they won’t break during firing; and took on the daunting process of building gas-fired kilns to replace Castle Clay’s original, which hadn’t been constructed correctly.

“You can’t really be a potter unless you know how to build your own kiln,” Jim insists. “And thanks to Castle Clay losing leases and having to move the studio, I helped build four giant kilns in a two-year period, right at the beginning of my career. At the time they were the largest kilns in Denver.”

“You can’t really be a potter unless you know how to build your own kiln,” Jim insists. “And thanks to Castle Clay losing leases and having to move the studio, I helped build four giant kilns in a two-year period, right at the beginning of my career. At the time they were the largest kilns in Denver.”

In Jim’s opinion, the fact that many of the other Castle Clay members relied on him instead of learning the skills themselves undermined their craft. “You need to understand how to alter the clay for your own unique effects. You can use local materials. That’s what Henry Mead, who founded Castle Clay, was all about-using the clay from his property in Castle Rock. A craftsman doesn’t just use something out of a plastic bag from somewhere east of the Mississippi. Be in charge of what you’re doing!”

The skills were invaluable, but Jim feels that acquiring them distracted from his own development. “The nature of Castle Clay was that I never had the peace of mind to crack that final secret of being a potter.”

Loomings

The other members of what by then had become a potters co-op relied on Jim, but not enough to pay him for his previous work. He was just green enough to think they would figure that out one day soon. So he eked out a living teaching pottery classes and selling what pots he had time to execute in semi-annual art shows and at several local galleries. Although his output was modest, his artfulness was there in every piece, which explains why some of them ended up on display in the Denver Art Museum.

At age 23 Jim was named president of the Castle Clay co-op (a job no one really wanted; the lawyer told him he was a perfect fit because “you have nothing to lose”). By then the members had coalesced into a few contentious groups, which situated Jim painfully in the middle. Close up, he would have looked like an Amazonian explorer in a leaky canoe, tilting through a muddy swamp full of frothing piranhas. But at the time friends like me stopped seeing Jim close up. We were all trying to invent our own lives, and from where we stood Jim’s life seemed to be a hippie idyll. We observed him from the cave-mouths of our particular situations and thought, “There’s a free man. If only I could be that free!”

At age 23 Jim was named president of the Castle Clay co-op (a job no one really wanted; the lawyer told him he was a perfect fit because “you have nothing to lose”). By then the members had coalesced into a few contentious groups, which situated Jim painfully in the middle. Close up, he would have looked like an Amazonian explorer in a leaky canoe, tilting through a muddy swamp full of frothing piranhas. But at the time friends like me stopped seeing Jim close up. We were all trying to invent our own lives, and from where we stood Jim’s life seemed to be a hippie idyll. We observed him from the cave-mouths of our particular situations and thought, “There’s a free man. If only I could be that free!”

The details are too torturous to deal with here, so suffice it to say that Jim’s life at Castle Clay went from bad to worse. By the time he cut his ties with the co-op it had consumed 15 years of his life and left him so embittered that he walked away from the craft of pottery as well—forever, or so he thought.

The Unknown Craftsman

The great truth of life is that nothing is wasted if you live long enough.

After leaving Castle Clay, Jim spent many years in the Denver Public Schools, primarily working with Special Education kids. He read books by the car load and shared his enthusiasms with his students, set up art studios at various schools and taught the basics of pottery, among other things. But whenever it crossed his mind to throw a pot or two, the bitterness over Castle Clay would wipe out the urge in a hurry.

After leaving Castle Clay, Jim spent many years in the Denver Public Schools, primarily working with Special Education kids. He read books by the car load and shared his enthusiasms with his students, set up art studios at various schools and taught the basics of pottery, among other things. But whenever it crossed his mind to throw a pot or two, the bitterness over Castle Clay would wipe out the urge in a hurry.

Jim’s life became a struggle in other ways, too. Not long after his Uncle passed away, his beloved father passed away as well—but not before giving Jim some solid advice: “Quit smoking, son. And for God’s sake, learn to have fun!” Jim couldn’t bear the idea of putting their homes up for sale, so he held onto them and became a landlord. Some years later his mother fell ill with Huntington’s disease, a degenerative illness that made Jim a caretaker for seven long years. He was willing and able, but the effort was all-consuming. He stopped writing poetry altogether, and stopped even thinking about pottery.

“Looking back,” he says, “I was incredibly lucky. What I’d learned about handling mentally challenged kids was a tremendous help in caring for my Mom.”

The death of his mother and attendant family turmoil left Jim mentally and emotionally exhausted. But one could say it left him open. About a year after her passing, in 2005, Jim was talking to a friend from Castle Clay days, a fellow potter named Chris who had spent the past couple of decades throwing pots in North Carolina and Massachusetts and was always after Jim to get back into the craft. Chris mentioned that she planned to call Carol, a mutual friend and Denver area potter who had worked with Jim on Castle Clay’s Kiln Committee, among other critical tasks. Thanks to Chris, Carol called Jim and mentioned that she had a kiln in need of repair.

The death of his mother and attendant family turmoil left Jim mentally and emotionally exhausted. But one could say it left him open. About a year after her passing, in 2005, Jim was talking to a friend from Castle Clay days, a fellow potter named Chris who had spent the past couple of decades throwing pots in North Carolina and Massachusetts and was always after Jim to get back into the craft. Chris mentioned that she planned to call Carol, a mutual friend and Denver area potter who had worked with Jim on Castle Clay’s Kiln Committee, among other critical tasks. Thanks to Chris, Carol called Jim and mentioned that she had a kiln in need of repair.

“I told her the Kiln Committee is back in business,” Jim says with a laugh. “Carol wouldn’t pay me for the kiln work, which turned out to be suspiciously minor, but she said I could use her clay and her studio to throw a few pots. Pretty clever! I’d had absolutely no intention of taking up clay again. But I did. And now look at me!”

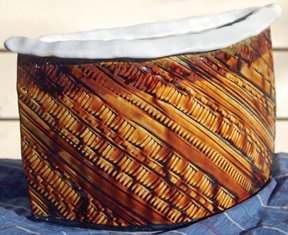

As a longtime friend I can attest that it’s a pleasure to look at Jim now. He’s in it, guided-and, as he points out, divided-by the ideals set forth in Soetsu Yanagi’s classic text, The Unknown Craftsman. Yanagi asserts the beauty of useful things over objects that exist only as art, and exalts the anonymous craftsman over the individualistic artist. Not that Jim is striving for anonymity, but he has taken to heart Yanagi’s injunction that “craftsmanship must not be impeded by individualism,” and his insistence that “if … a craft object becomes unsuitable for our daily living, it fails of its purpose.” Jim is striving to combine the “artlessness” of utilitarian-ware with a limited production of hand-built and wheel-thrown objects, seeking ”balance” between the intrinsic possibilities of the material and the need to create accessible, useful work.

As a longtime friend I can attest that it’s a pleasure to look at Jim now. He’s in it, guided-and, as he points out, divided-by the ideals set forth in Soetsu Yanagi’s classic text, The Unknown Craftsman. Yanagi asserts the beauty of useful things over objects that exist only as art, and exalts the anonymous craftsman over the individualistic artist. Not that Jim is striving for anonymity, but he has taken to heart Yanagi’s injunction that “craftsmanship must not be impeded by individualism,” and his insistence that “if … a craft object becomes unsuitable for our daily living, it fails of its purpose.” Jim is striving to combine the “artlessness” of utilitarian-ware with a limited production of hand-built and wheel-thrown objects, seeking ”balance” between the intrinsic possibilities of the material and the need to create accessible, useful work.

The Craft of New Beginnings

Several lost arts surfaced thanks to Jim’s rediscovery of the pleasures of clay. Poetry was one of them. He unearthed poems he’d written in Ohio and realized they made an almost complete book, and found there was also a handful of poems about pottery, from his first encounters with the craft. Suddenly he saw that the handful could expand into a book of its own. Jim’s pottery poems are substantial, whimsical, philosophical, even semi-mystical. In one, an homage to Soetsu Yanagi entitled “The Unknown Craftsman,” he notes:

the true work

is dialogue

between hunger

& dream,between clay

& learning child,between brief vision

& deep habit;the true work

disappears

in the hand,leaving

completion & wonder;reminding us:

this privilege

this discipline

this journeyunfolds

unknown

even

to its maker

Poem after poem bristles with craft insights, life-wisdom, and self-effacing humor.

The second lost art was the art of human relations. Jim’s time without pottery had been years of withdrawal, combined with an intense focus on becoming versatile and effective in his classroom role. But now the shell was off. He reconnected with a friend from his Castle Clay days, Sue Howell, herself a potter with a vintage cabin in the mountains southwest of Denver and a kiln Jim had helped her build some years ago. They had moved in and out of each other’s orbit over the years, but the emotional weather was always against them. Now, quite suddenly, they find themselves inhabiting the same season.

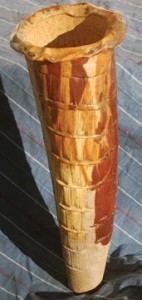

Of course, new beginnings always come at a cost. A short time back, Jim’s closest, steadiest friend from high school called him with some disturbing news. The classic Northwest Denver home Tom had grown up in—and which, after the deaths of his parents, he and his siblings had been forced to sell—was gone. The house had ended up in the hands of a developer, who in turn simply scraped it off the face of the Earth: the home itself and fifty trees his grandparents had planted by hand—a century’s heritage—all reduced to scrap and splinters in a matter of hours. Tom was heartbroken and so was Jim. But Jim brought his hard-won wisdom to bear on the situation, and with Tom’s help filled his car with chunks of the massive sycamore and larch that had been among the first trees planted on the property.

Of course, new beginnings always come at a cost. A short time back, Jim’s closest, steadiest friend from high school called him with some disturbing news. The classic Northwest Denver home Tom had grown up in—and which, after the deaths of his parents, he and his siblings had been forced to sell—was gone. The house had ended up in the hands of a developer, who in turn simply scraped it off the face of the Earth: the home itself and fifty trees his grandparents had planted by hand—a century’s heritage—all reduced to scrap and splinters in a matter of hours. Tom was heartbroken and so was Jim. But Jim brought his hard-won wisdom to bear on the situation, and with Tom’s help filled his car with chunks of the massive sycamore and larch that had been among the first trees planted on the property.

“I’m going to burn the wood and make an ash glaze from it,” Jim says, “and use it to glaze some remembrance pots for the family. It’s such a small gesture, but it’s a new beginning—a bridge—a seed toward future things.”

The pots will have the beauty of usefulness, as Yanagi requires, and something more: the beauty of skilled work lovingly done.

“I’m thankful,” Jim says. “It’s so good to have the skills, and the time, and the peace of mind to put them to use for something that’s deep and meaningful. It’s all part of my own exploration.”

The goal of that exploration isn’t easy to describe. It’s partly a search for work that has heart, embodying richness, subtlety and imagination. Jim says it’s a matter of “finding ways and making places for clay to do clay-like things.” It’s a journey with no real end, only process: a way of letting shape, color and texture arise from the happenstance of each formative encounter, each firing; a way of revealing the beauty and complexities of the material and its uses.

________________________

Jim Bednar can be reached by calling 303.433.6776 or by emailing showell@idcomm.com.

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

Joe, I was thinking: Part of me embraces the idea of poetry being useful — in fact, it insists that poetry <I>is</I> useful, and always has been, even if not in any practical hammer-and-nails sort of way. Anything that helps us see or feel or understand, anything that reminds, anything that takes us away from ourselves and into the larger human and natural sphere, is useful.<BR/><BR/>Meanwhile,

What a nice article!