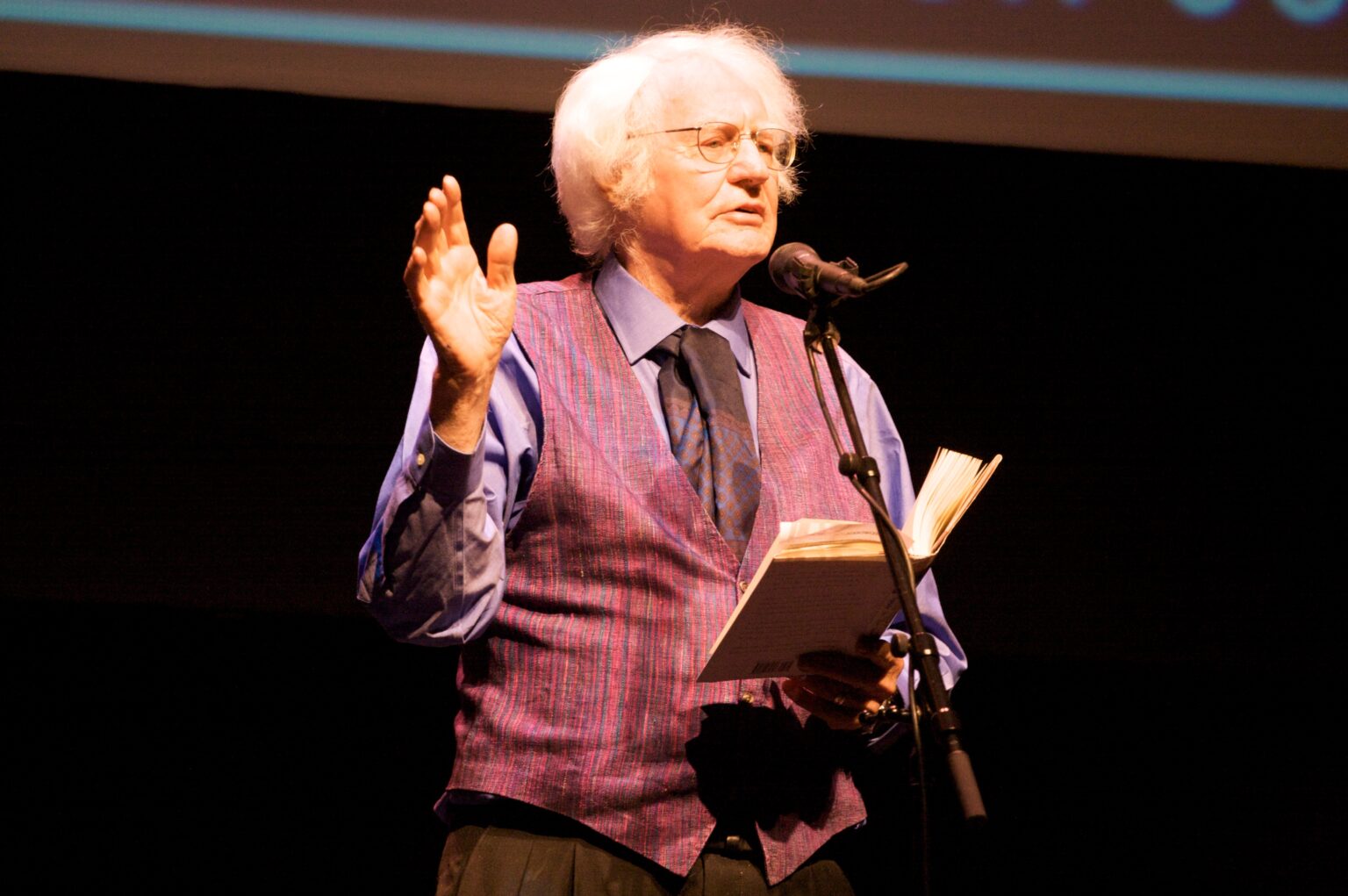

Poetry Out Loud Minnesota Finals at the FItzgerald Theater. Desdemona was the MC, and Robert Bly (Minnesota Poet Laureate) read several of his poems at the end. Two of the 18 competitors were from Morris and both made it to the last round of 6; Alex McIntosh placed 4th and Thomas McPhee placed 6th. Nic McPhee, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

It’s startling to think of Robert Bly moving on, leaving us here without his energy, his restlessness, his exemplary dedication to opening a path toward a different way of imagining the purpose of poetry.

Dana Gioia famously asked, “Can poetry matter?” Bly showed that it could matter … that poetry provided a way into the reaches of spiritual life that had been hidden away from us by America’s utilitarian values. My friend and fellow poet, Bill Tremblay, tells the story of approaching Bly at a conference of some kind and saying, “Without you there would be no American poetry as we know it.” How true! Robert Bly didn’t accomplish that entirely on his own, of course, but his genius was central to the effort.

Bly opened up the possibility for me of being a poet and dedicating the majority of my writing life to that endeavor. He was, in fact, the first living poet I ever saw in person—and what an experience that was! (I wrote about it in some detail back in 2009.) I had come to poetry in high school through Laurence Perrine’s textbook Sound and Sense, and it was for me very much a “head” experience; analysis first, then feeling. Bly’s performance pushed analysis to the side and brought feeling into the foreground. Feeling first, then analysis; the experience first, then the interpretation. Bly changed the way I read poetry and the way I wrote poetry, and he did so not just through his own poems but through his translations, which in itself helped to break the stranglehold of necktied, smug 1950s verse. (We’ve moved on to another kind of smugness, but ain’t that the American way?)

Here are some of the obits for Robert Bly, most of them skewed toward often skewed considerations of the Men’s Movement and Iron John:

https://www.theguardian.com/global/2021/nov/23/robert-bly-obituary

https://www.latimes.com/obituaries/story/2021-11-22/robert-bly-poet-dead

https://chicago.suntimes.com/2021/11/22/22797012/robert-bly-dead-iron-john-author-obituary-poet

It will take a remembrance by someone who understands the full range of Bly’s importance to American literary culture to provide a genuine sense of his achievement. In the meantime, here is the most capacious source I know of on Bly and his work: Robert Bly in This World: Proceedings of a Conference Held at Elmer L. Andersen Library, University of Minnesota, April 16-19, 2009, edited by James Lenfestey and Thomas R. Smith.

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

I’d dispute the term “cant,” Daniel. (“Hypocritical and sanctimonious talk.”) Bly rightly skewered the dead-end formalism of 1950s poetry, which all too often clothed itself in forms that amounted to little more than Halloween dress-up. But he didn’t attack only Eliot and Pound, Ransom and Eberhart and Wilbur, but Olson and even W. C. Williams, who he loved. He did so not to expunge their work from the scene but to call its premises into question. That questioning was necessary to poetry and the poets trying to write it. There is, after all, no inherent value in formal verse, just as there is no inherent value in improvisational (a.k.a. “free”) verse. But it’s in part thanks to Bly that we have poets today like Amit Majmudar, who writes with great assurance in both modes, or the highly formal but iconoclastic poetry of Tina Chang. Not that they would claim Bly as a member of their personal lineage; I have no idea if either one would cite him as an influence. But the ground they’re working was made arable by him and others in his rather vast circle. Bly was no enemy of form, only of empty form. He located the value of poetry elsewhere, and yes over time, as the climate of poetry changed, Bly moderated his views. He himself wrote in forms, albeit forms of his own creation—his ramages and his version of the ghazal in tercets instead of couplets. We were lucky to have had him in our midst!

You’re right, Jonah, that his late poems are among his best and among the best of his generation, though they’re generally overlooked. I think his allusiveness in the late ones has kept serious critics at bay. I read an interview somewhere in which he was asked about that—something about how many arcane references he makes in the late poems. Won’t that frustrate readers? And he said something like: “It’s not my job to make up for what a reader didn’t learn in high school.” Hah!

Pat, I’m glad you could finally post! Not sure what they did behind the scenes, just glad it worked. Yes, Bly is certainly sailing on, but not on the surface. “… at last, the quiet waters of the night will rise, / And our skin shall see far off, as it does underwater.” There’s a wonderful recording of the sonorous Garrison Keillor reading the poem those lines come from here: https://writersalmanac.publicradio.org/index.php%3Fdate=2014%252F04%252F06.html. The poem begins are 3:13 or so.

Sail on, Robert Bly!

Robert Bly, the last of the great American poets born between 1925 and 1929. What a family they were:

Carolyn Keizer, Koch, Kumin, Stern, Ammons, Creeley, Merrill, O’Hara, Ashbery, Kinnell, Merwin, Wright, Hall, Levine, Sexton, Rich.

Hugo, Dickey, and Levertov were born a couple years before. Haydn Carruth a couple before them.

After Merwin died, I think I was holding my breath a little. Bly was the one poet left from his generation of poets. His late poems were among his best. His presence in this world will be missed.

Besides his great poems, he introduced American readers to poets like Vallejo, Jimenez, Machado, Neruda, Kabir, Ghalib, and others.

Robert Bly was a gift.

I have some mixed feelings about the man’s impact on American poetry, but I appreciate that he moderated his ideological cant against formal verse as he grew older and his later work, like Morning Poems, was outstanding.