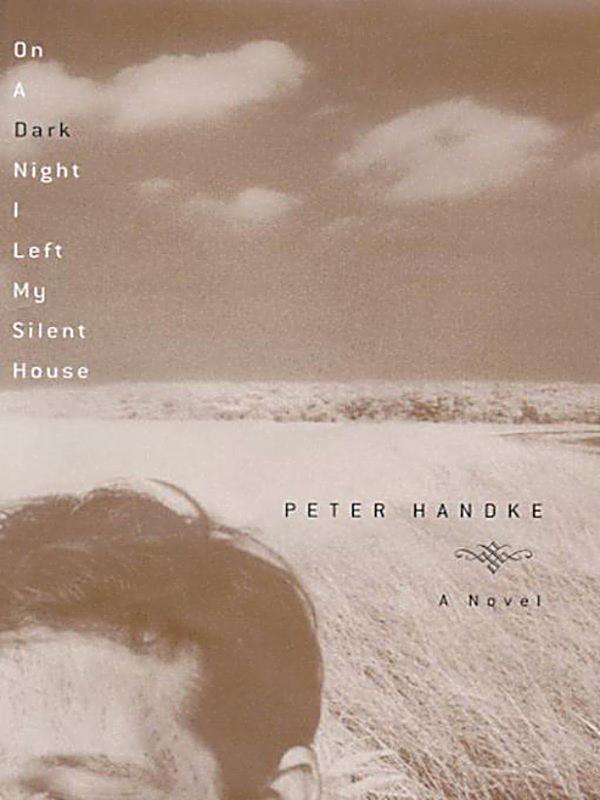

I recently finished a typically soulful, visionary novel by Peter Handke, On a Dark Night I Left My Silent House. It concerns the journey of a pharmacist from the Austrian town of Taxham, near Salzburg, who—isolated and estranged from his wife—sets out to cure himself of anxiety and dread by undertaking a long, strange journey into the Alps. There he acquires two traveling companions, and aging and all-but-forgotten poet and a once-famous Olympic skier, each on his own quest. After passing through a series of tunnels, they find themselves in a foreign country that may or may not be Spain; in any case, he ends up venturing into the steppe, where his own quest finds what amounts to spiritual peace.

I’m attempting to share enough to give a sense of the book without giving anything essential away. Enjoy!

* * *

“It’s not true,” the poet commented, “that Narcissus was in love with his own reflection. What actually happened is that he was gifted or cursed with an overwhelming love for the world. He was born and grew up filled with tenderness toward all beings and phenomena, from his fingertips to the most remote corners of the universe.Young Narcissus was the soul of devotion and affection, and wished for nothing more than to take the whole world in his arms. Bu the world, at least the human world, didn’t permit that, recoiled from him, didn’t return his loving gaze.His enthusiasm for existence and his devotion to the known and unknown alike couldn’t find an anchor anywhere. And so, as time passed, he had to find an anchor in himself. And so Narcissus, that great lover of the world, clung to himself. And so he ultimately came to grief.”

pp. 89-90

Here there was a curious back and forth between the seasons, one minute way ahead, the following just as far back. On one of the days there the storyteller went for a swim in the river, the one that had more water, with the whispering or rustling of the poplars on both banks and that summery sound of crickets chirping, if there ever was one, and all of a sudden—he was swimming upstream—a seemingly unending deluge of fallen leaves swept toward him, yellow, red, blackish, an interminable train, drifting on and under the water in garlands, which further reinforced the autumnal impression—while in the next moment a cuckoo could be heard, as if it were at most late spring.

And that mulberry tree that still had almost all its fruit, most of it unripe, while the one in Taxham had long since dropped all its berries, and even the red stains on the ground had long since faded. And likewise the elderberry here, blooming in cream colored dots, while in that same instant your eye lit on the sunflower fields, blackened as in November and reminiscent of the world-war cemeteries, above which, however, midsummer air still shimmered.

pp. 116-117

“Just as my master Paracelsus said, in his fragment on mushrooms: He who catches sight of something precious is, in the same moment, already on the lookout for the next precious thing.”

pp. 181

And from then on my questions were limited almost entirely to “And?” — “And?” — The pharmacist: “One day she’ll come into my house, the woman who’s not my enemy.”— “And?” —Don’t you feel this, too? It’s as if there were no one left of my own age: People either all seem much older than me or much younger.” — “And?” —“Yet I feel a growing-old in myself, in that my energy, which continues to be there, perhaps stronger than ever, is no longer accompanied by any drive to actualize it. Something lies before me, seemingly expecting me to get it going,and I walk right by it.: — “And?” — “A person usually remembers how a dream ended. Almost never how it began!”

pp. 182

The pharmacist’s song, “which sounded as though it had been in preparation a longtime and practiced in private”:

They fell into each other’s arms with unspeakable weakness.

They had unspeakable joy of one another.

They lay together in unspeakable exhaustion.

They awoke in unspeakable amazement.

They looked out all the windows with unspeakable impatience.

They drove on with unspeakable patience.

They loved one another unspeakably.

They grew unspeakably free with one another.

They grew unspeakably bold with one another.

They grew unspeakably grateful with one another.

They rewarded one another unspeakably.

They perspired,

shouted,

wept,

bled,

fell silent and

told each other unspeakable stories.

They parted in unspeakable sadness.

They went in different directions

in unspeakable anger

at the unspeakable.

pp. 182-183

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

[…] with my previous Peter Handke post, I’m sharing enough of this remarkable collection by Samuel Menashe to give a sense of his […]