|

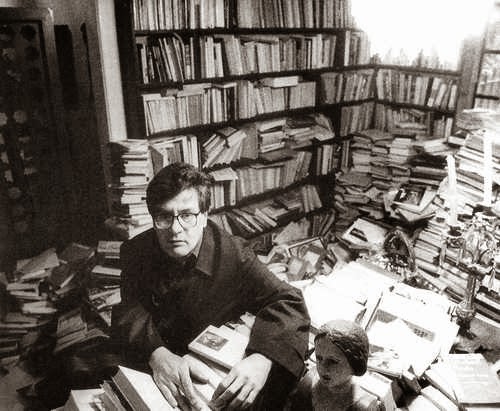

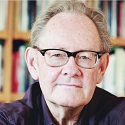

| José Emilio Pacheco—poet, writer, essayist, and translator—in his library. |

A few days ago I heard from Angela Mairead Coid, wife of my poetic mentor George McWhirter, that on Friday, January 24, the Mexican literary giant José Emilio Pacheco had fallen and struck his head, but appeared to be in no pain; he could not be awakened the next day, however, and passed away the day after—Sunday—from cardiac arrest. Pacheco was 74.

The news was delivered by way of this article in the student newspaper at University of British Columbia, where George taught for many years and where he met Pacheco in 1968, when he was teaching in the university’s Hispanic and Italian studies department.

|

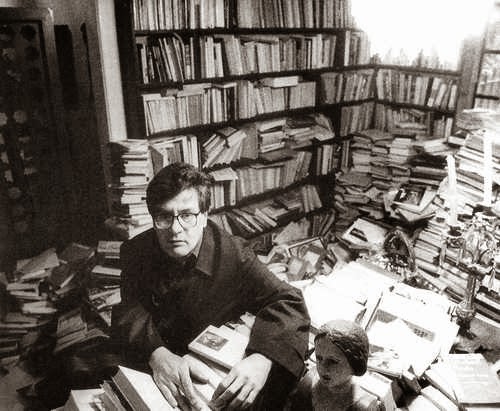

| Available from New Directions |

The great poet’s death came was a blow to both George and Angela. George has been translating Pacheco for decades; in 1987 New Directions published his edition of Pacheo’s Selected Poems, a generous anthology of poems published in Spanish between 1958 and 1983. The vast majority of translations in the book are George’s own.

Here is one of my favorites from that collection, Englished by George:

INSISTENCE

Let’s talk about snow once more let’s say

its cardinal virtue is that it’s quiet

It knows how to be born with impeccable smoothness in

the night

and when we wake we see it has claimed

the earth and the trees.The snow that is all around you today, where will it go?

The snow that spins interminably about the city

and the house

will take off into thin air

again be cloud and water

then snow once moreYou don’t have its easy adaptable nature

You’ll go on and die and be buried

You will be the clod of earth the snow settles on

|

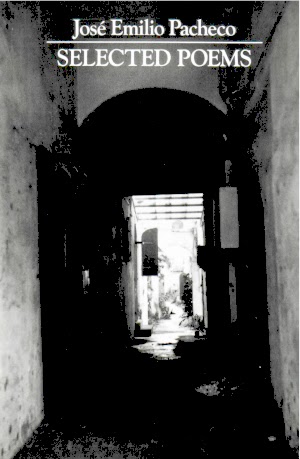

| Available from City Lights |

Another major collection of Pacheco translations, City of Memory and Other Poems, includes two complete books: I Watch the Earth: Poems 1983-1986, and City of Memory: Poems 1986-1989. The former is translated by David Lauer, the latter by Cynthia Steele. Among my favorites is this one, in Steele’s translation:

A DOG’S LIFE

We despise dogs for letting themselves

be trained, for learning to obey.

We fill the noun dog with rancor

to insult each other.

And it’s a miserable death

to die like a dog.Yet dogs watch and listen

to what we can’t see or hear.

Lacking language

(or so we believe),

they have a talent we certainly lack.

And no doubt they think and know.And so

they probably despise us

for our need to find masters,

for our pledge of allegiance to the strongest.

|

| Pacheco receiving the Cervantes Prize at the University of Alcalá de Henares, April 23, 2010 |

There is simply no kind of poem Pacheco did not write: lyrics, lyric sequences, narratives, philosophical verse, satires—all humble and humbling in their directness and lack of both theoretical jargon and political cant. The poet’s obituary in La Jornada captures Pacheco’s personality, especially when it quotes his reaction to the publication of his massive Sooner or Later (Tarde o temprano): Poems 1958-2009 by Fondo Cultura Económica:

“I never thought I would write a book of 800 pages,” he said. “I must be very fruitful, but no, it isn’t fertility, it’s an abundance of time. Eight hundred pages in 50 years are no more than 15 pages a year. They could say, ‘This guy doesn’t write anything.'” He’d said much the same thing a few days earlier at the International Book Fair in Guadalajara, upon receiving the Queen Sofía Prize, but in that speech he’d added: “How I wish that the product of all that effort and perseverance may be, in the end, ten valid poems.”

Angela, in her email to me, remarked that “José Emilio Pacheco was Mexico’s Seamus Heaney.” High praise from a woman who, like her husband, has remained distinctly Irish after almost 50 years in Canada!

In any case, what a privilege it’s been for me to spend time with Pacheco through his work. Read more about this extraordinary writer here, here, and here.

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.

Joseph Hutchison, Colorado Poet Laureate 2014-2019, has published 20 collections of poems and edited or co-edited three poetry anthologies. He currently directs two master’s-level programs for University College at the University of Denver: Professional Creative Writing and Arts & Culture Management. Joe lives with his wife, Melody Madonna, in the mountains southwest of Denver, Colorado, the city where he was born.